Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in Sub-Saharan Africa Health Financing Decisions Systematic Review

Public HealthReceived 19 Aug 2025 Accepted 26 Aug 2025 Published online 27 Aug 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

In What Way Does Climate Change Matter!?

Received 19 Aug 2025 Accepted 26 Aug 2025 Published online 27 Aug 2025

Background: Health Technology Assessment (HTA) is increasingly recognized as a critical tool for evidence-based health financing decisions in Sub-Saharan Africa. However, its adoption is influenced by a variety of factors. This study synthesizes evidence from the literature on the factors enabling and hindering HTA institutionalization in the region as a means of supporting universal health coverage (UHC).

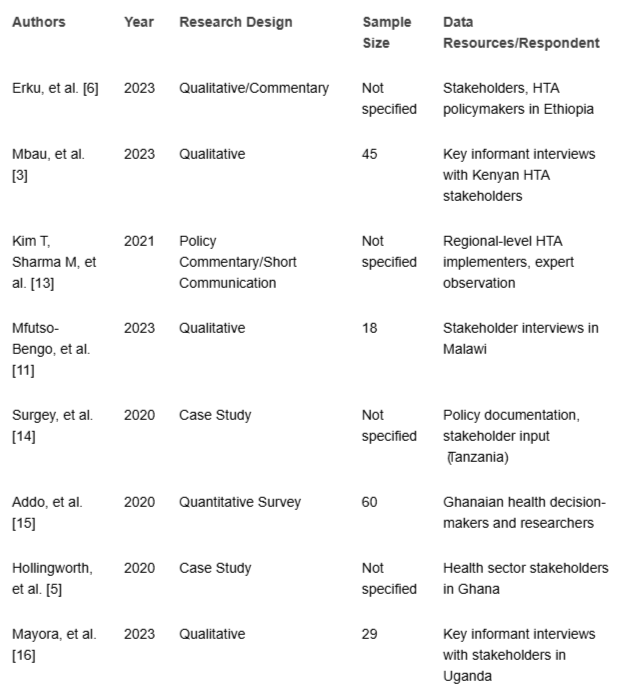

Methods: A systematic analysis of eight country-specific nonsystematic review studies covering Ethiopia, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Ghana, and Uganda was conducted. The studies employed qualitative (n = 5), mixed-methods (n = 1), cross-sectional survey (n = 1), and descriptive analysis (n = 1) approaches, with sample sizes ranging from 20–60 stakeholders, including policymakers and health professionals. Barriers and enablers were categorized into five themes: human resource capacity, financial and infrastructural constraints, policy and governance frameworks, stakeholder engagement and political will, and data and evidence availability.

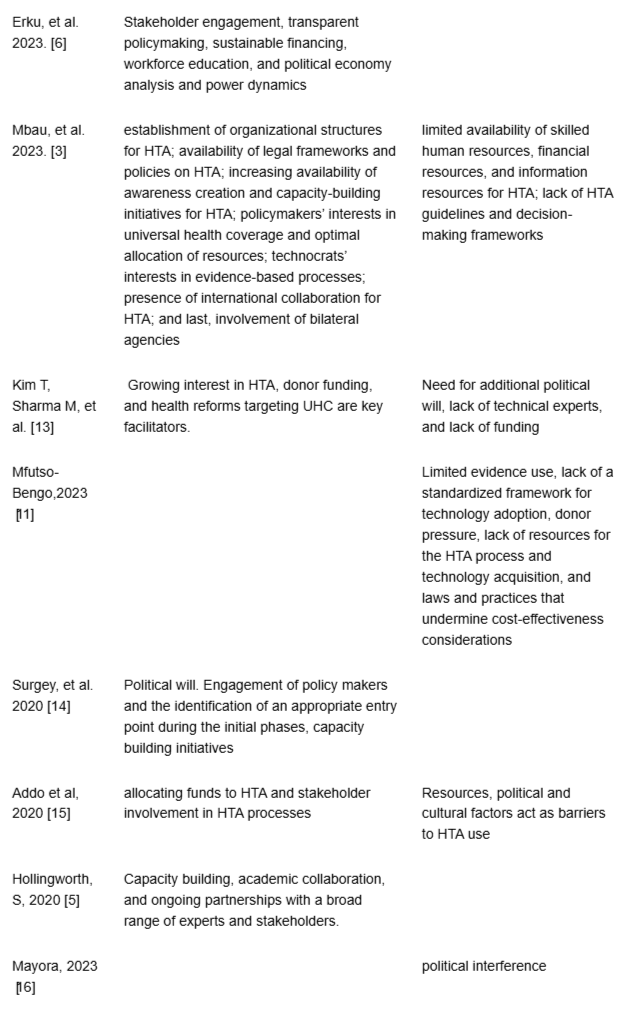

Results: Seventeen barriers and sixteen enablers were identified. The key barriers included limited technical capacity (5 studies), financial constraints (4 studies), a lack of standardized HTA frameworks and guidelines (3 studies), political interference (1 study), limited evidence use (1 study), and cultural/legal challenges (1 study) The enablers included stakeholder engagement (3 studies), political will and UHC alignment (2 studies), capacity building (3 studies), legal/institutional frameworks (2 studies), international collaboration (2 studies), and transparent policymaking (1 study). Countries such as Kenya and Ethiopia have progressed through institutional structures and international support, while resource and governance challenges have persisted across contexts.

Conclusion: HTA adoption in Sub-Saharan Africa is hindered by human resource shortages, funding limitations, and weak governance, but facilitated by stakeholder engagement, political commitment, and international partnerships. Tailored interventions, including capacity building, sustainable financing, and standardized frameworks, are essential for institutionalizing HTA and advancing evidence-based health financing for UHC. Future research should explore underrepresented countries and employ longitudinal designs to increase generalizability.

Health technology assessment (HTA) remains a significant process in evaluating the value of health technologies to inform health financing decisions in resource-constrained settings. HTA offers a critical tool to prioritize interventions and achieve universal health coverage (UHC) []. Additionally, HTA can facilitate evidence-based decision-making, thereby promoting more efficient resource allocation and improved health equity []. However, despite this potential, HTA adoption and implementation are marred by many challenges, including limited awareness among policymakers, inadequate institutional support, gaps in technological infrastructure, and a lack of reliable local data []. These barriers hinder the systematic integration of HTA into health policy and funding frameworks, resulting in decision-makers relying on traditional methods that may not effectively address the region's health priorities. For instance, studies show that in many Sub-Saharan African countries, health financing decisions are often influenced more by political agendas, donor priorities, and historical budgeting practices than by structured economic assessments such as Health Technology Assessment (HTA) [].

Health technology adoption and implementation in low-resource settings face critical challenges, including data scarcity, weak health information systems, and fragmented governance structures. Similar challenges were observed in Kenya’s devolved health system, where fragmented governance and limited information availability hindered equitable and evidence-based health priority setting []. The lack of high-quality, locally relevant data and limited access to usable health information impede the ability to conduct robust HTAs []. Additionally, the shortage of professionals skilled in HTA methodologies hinders the reliability of assessments, as seen in countries such as Nigeria and Malawi []. Fragmented decision-making processes across various sectors and government levels further decrease the consistency and effectiveness of HTA application [].

Despite these challenges, there is growing adoption and institutionalization of HTA in most African countries. The increasing political commitment in countries such as Kenya and Ethiopia, where national structures for HTA are being established, shows that there is a shift toward more evidence-informed policymaking and decision-making. Capacity-building efforts have been supported through regional collaboration and international support []. Additionally, countries such as Ghana and South Africa have begun integrating HTA-like processes into the design of health benefit packages, signalling a broader commitment to institutionalising HTA as a strategic tool for health financing. Collectively, these developments suggest that while barriers remain, enablers present promising pathways for embedding HTA into health system governance in SSA.

This paper examines the key barriers to and enablers of HTA adoption in SSA, offering insights into strategies for integrating HTA into health financing decisions to optimize resource allocation and improve health outcomes.

The researcher undertook a systematic literature review of national and international literature with the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).

This review included studies conducted in Sub-Saharan African countries that examined only barriers, enablers, or factors for the adoption, implementation, or institutionalization of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in health financing decisions. Eligible studies focused on national or subnational health systems and reported structural, political, economic, or capacity-related factors influencing HTA uptake. Eligible studies were primary research or case studies (qualitative, mixed-methods, surveys, or descriptive analyses), excluding systematic reviews. Studies had to provide clear findings on HTA-related processes and be published in peer-reviewed journals in English between January 2010 and April 2025. Only those offering sufficient contextual and methodological detail for data extraction and synthesis were selected.

An in-depth literature search was conducted across six databases (PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, CINAHL, Google Scholar, and Africa-Wide Information) using Boolean combinations of terms related to HTA, barriers/enablers, and sub-Saharan African health financing. The search terms combined keywords and phrases across four main concepts: HTA (“health technology assessment,” “evidence-informed policy”), barriers and enablers (“barriers,” “facilitators,” “challenges,” “drivers,” “constraints”), health financing decisions (“health financing,” “resource allocation,” “priority-setting,” “health policy”), and geographic scope (“Sub-Saharan Africa,” and specific country names such as Kenya, Ethiopia”).

The strategy applied filters to include only studies published from January 2010 to April 2025 in English and was limited to empirical research, case studies, or policy briefs with original data. Additional sources included gray literature from organizations such as the WHO, World Bank, iDSI, and HTAi, along with hand-searching reference lists and contacting regional HTA experts. This multisource, multimethod approach ensures the broad and rigorous identification of relevant studies.

Data extraction was conducted systematically via a predesigned data extraction form to ensure consistency and comprehensiveness across studies. The form captured both bibliographic and thematic information. The key data elements extracted from each included study were (1) author(s) and year of publication, (2) country or countries of focus, (3) study objectives, (4) study design and methodology (e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed methods), (5) data sources (e.g., interviews, surveys, document review), (6) type of stakeholders involved (e.g., policymakers, researchers, funders), (7) key barriers to HTA adoption, (8) key enablers, and (9) reported outcomes or recommendations. Two reviewers independently extracted data from the studies, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. The extracted data were entered into a spreadsheet and organized by themes for synthesis and analysis.

The researcher employed the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for a qualitative study, focusing on the clarity of the research aims, appropriateness of the methodology, rigor of the data collection and analysis, reflexivity, and ethical considerations. Quantitative and mixed-methods studies were assessed via the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT, 2018 version), which evaluates the clarity of research questions, appropriateness of measurements, completeness of outcome data, and risk of selection, performance, and reporting bias.

Each study was independently assessed by two reviewers. Scores or judgments (e.g., low, moderate, or high risk of bias) were assigned for each criterion. Discrepancies in scoring were resolved through consensus or the involvement of a third reviewer. While studies were not excluded based on only quality assessment outcomes, the risk of bias ratings informed the strength of evidence during synthesis and interpretation. Overall, most studies demonstrated moderate methodological quality, with common limitations, including a lack of transparency in sampling, potential selection bias, and limited generalizability due to context-specific findings

(Table 1).

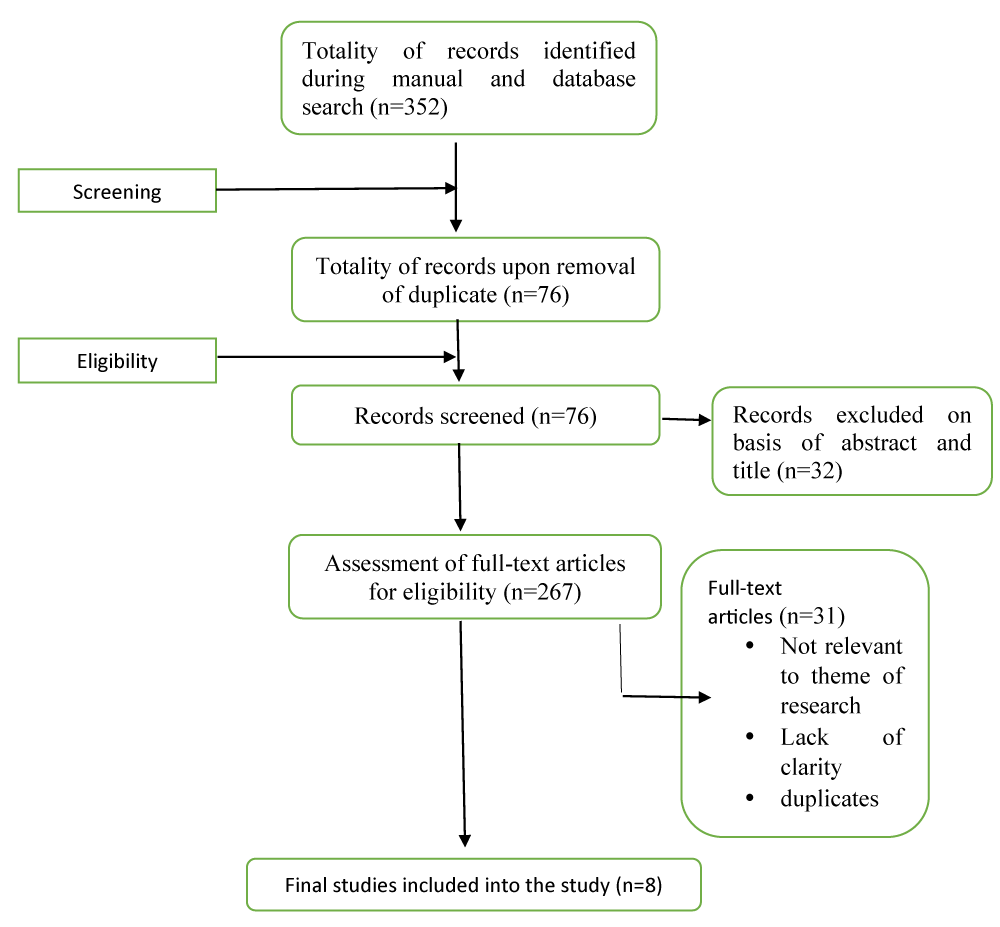

The initial systematic search yielded 352 records from electronic databases, including PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar, via combinations of search terms such as "Health Technology Assessment", "HTA", "adoption", "implementation", "barriers", "enablers", "Sub-Saharan Africa", and "health financing decisions". Gray literature and relevant institutional websites (e.g., the WHO, iDSI, and World Bank) were also searched to ensure the inclusion of unpublished or policy-relevant reports.

After 85 duplicates were removed, 267 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Of these, 31 full-text articles were retrieved for detailed review on the basis of predefined eligibility criteria. Following the full-text assessment, 8 studies met the inclusion criteria and were selected for the final synthesis. Erku, et al. [], Mbau, et al. [], Kim T, et al. [], Mfutso-Bengo, et al. [], Surgey, et al. [], Addo, et al. [], Hollingworth, et al. [] Mayora, et al. []. These included country-specific case studies from Ethiopia, Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, Malawi, South Africa, and Tanzania, and one multi-country study, all published between January 2010 and 2025 (Figure 1)(Tables 2,3).

|

Study |

Country |

Frequency |

|

Erku, et al. [] |

Ethiopia |

1 |

|

Mbau, et al. [] |

Kenya |

1 |

|

Kim T, Sharma M, et al. [] |

Keya, Zambia |

1 |

|

Mfutso-Bengo, et al. [] |

Malawi |

1 |

|

Surgey, et al. [] |

Tanzania |

1 |

|

Addo, et al. [] |

Ghana |

1 |

|

Hollingworth, et al. [] |

Ghana |

1 |

|

Mayora, et al. [] |

Uganda |

1 |

|

Total |

|

8 |

Analysis results

|

Enabler Category |

Description |

Studies Reporting |

|

Stakeholder Engagement |

Active involvement of policymakers, technocrats, academia, and international donors was emphasized. |

5, 2, 4 |

|

Political Will & Policy Alignment |

Alignment with universal health coverage (UHC) agendas and political interest in efficiency supported HTA uptake. |

11, 12 |

|

Capacity Building & Training |

Skill development, academic collaboration, and workforce education enhanced readiness. |

4,5,2 |

|

Legal and Institutional Frameworks |

The establishment of HTA units and supportive policy/legal frameworks was a key structural enabler. |

2,13 |

|

International Collaboration and Donor Support |

Partnerships with bilateral agencies and global HTA networks facilitated technical and financial support. |

11, 4 |

|

Transparent Policymaking |

Clear processes for evidence appraisal and priority setting were emphasized. |

5 |

|

Barrier Category |

Description |

Studies Reporting |

|

Human Resource Constraints |

Shortages of trained HTA experts limited implementation. |

2, 11 |

|

Lack of Financial Resources |

Limited national funding for HTA activities hindered sustainability. |

10, 13 |

|

Absence of Frameworks and Guidelines |

The lack of standardized HTA methodologies and policy frameworks reduced uptake. |

10, 2 |

|

Political Interference |

Decision-making is influenced by political interests instead of evidence. |

14 |

|

Limited Use of Evidence in Decision-Making |

Preference for ad hoc or donor-driven decisions without formal evidence synthesis. |

10 |

|

Cultural and Legal Challenges |

National laws and institutional cultures that deprioritized cost-effectiveness in health decision-making. |

13 |

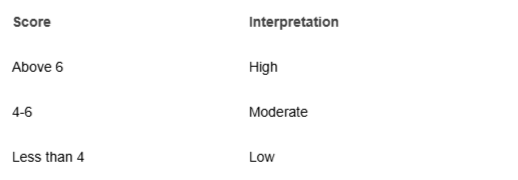

The study quality was assessed on a modified form of the Newcastle‒Ottawa Assessment Scale for Nonrandomized Studies (NRS). The outcome of the quality assessment of the studies used for the review is as follows:

|

Score |

Interpretation |

Absolute Frequency of Studies in the Category |

Relative Frequency of Studies in the Category (%) |

|

Above 6 |

High |

3 |

37.5% |

|

4–6 |

Moderate |

5 |

62.5% |

|

Less than 4 |

Low |

0 |

0% |

|

Total |

|

8 |

100% |

Stakeholder engagement is widely recognized as a significant enabler of HTA adoption in sub-Saharan Africa. Evidence from Ghana, Kenya, and Ethiopia shows the importance of involving policymakers, technocrats, academics, and international donors in the design and implementation of HTA processes []. This aligns with Oortwijn, et al.’s assertion that broad stakeholder collaboration is essential to strengthen HTA in LMICs []. Studies from Ethiopia further emphasize that inclusive participation fosters transparency and accountability in decision-making []. However, engagement is not without challenges. Kaló, et al. caution that competing interests, particularly from industry, can undermine collaboration, a concern reflected in Kenya, where inconsistent evidence use has weakened HTA’s influence []. These dynamics suggest that while stakeholder involvement is a key enabler, structured mechanisms to manage conflicts are equally vital for sustainable HTA uptake.

Political Will and Policy Alignment: The alignment of HTA with UHC agendas and political support has been identified in two studies as an enabler of HTA adoption. This finding agrees with Chalkidou, et al.’s finding that political commitment is critical for prioritizing evidence-based resource allocation []. Additionally, Surgey, et al. highlight Tanzania’s political will as a facilitator for establishing an HTA committee, a perspective also shared by Wilkinson, et al. who advocate aligning HTA with national health priorities []. Conversely, Drummond, et al. caution that political will can be undermined by short-term electoral pressures [].

Skill development, academic collaboration, and workforce education were identified as enablers in three studies and are widely recognized as enablers of HTA adoption []. Uzochukwu, et al. emphasized that training programs enhance local expertise, a view supported by Hollingworth, et al. in Ghana, where academic partnerships facilitated HTA readiness []. However, MacQuilkan, et al. argued that overreliance on international training may limit local sustainability [].

Legal and institutional frameworks are central to the institutionalization of HTA in sub-Saharan Africa. The establishment of HTA units and supportive policies, as highlighted in Ghana and Kenya, illustrates how structural arrangements can provide legitimacy and continuity for evidence-informed decision-making []. Kenya’s Medicines and Technology Assessment Committee, for instance, represents a key institutional enabler. Similarly, Pitt, et al. emphasize that such arrangements enhance transparency and accountability in resource allocation []. However, institutionalization remains unevenly, as noted by Filby, et al. who caution that resource constraints frequently undermine implementation, a challenge witnessed in Ghana, where, despite growing interest, the absence of a formal HTA body has slowed progress []. These experiences suggest that while frameworks are important, their effectiveness ultimately depends on sustainable financing and capacity support.

International Collaboration and Donor Support: Partnerships with bilateral agencies and global HTA network support have been identified in two studies as enablers of HTA adoption []. These findings are supported by Chalkidou et al, who noted that international support provides technical and financial resources for HTA in LMICs []. Hollingworth, et al. emphasize that donor-driven partnerships in Ghana have become a significant strategy in implementing the HTA process. Donor support has helped finance pilot assessments, training, and institutional capacity-building initiatives []. Conversely, Oortwijn, et al. warned that donor dependency may undermine local priorities, a risk not explicitly addressed in the studies but relevant to their focus on external support []. This debate highlights the need for balanced partnerships that strengthen local HTA capacity without compromising autonomy.

Transparent policymaking: Transparent policymaking is essential for enhancing the legitimacy and sustainability of HTA. In Ethiopia, Erku, et al. emphasize the use of political economy analysis to promote transparency []. Nemzoff, et al. argue that transparency fosters trust among stakeholders by making processes and criteria explicit, thereby reducing the risk of decisions being perceived as politically or donor-driven []. Beyond improving accountability, transparent processes ensure that scarce resources are allocated on the basis of evidence rather than competing interests, ultimately supporting HTA institutionalization. However, Kaló, et al. caution that entrenched political interests can undermine transparency, a challenge echoed in other studies, underscoring the need for robust governance mechanisms to safeguard HTA from interference [].

Shortages of trained HTA experts, reported in two studies, are a well-documented barrier in LMIC health systems []. Uzochukwu, et al. confirm that limited expertise hinders evidence-based decision-making, a challenge echoed by Mbau, et al. in Kenya []. These shortages of human resources are further exacerbated by brain drain 21. The shortage of trained HTA experts is not unique to Africa but reflects a broader global challenge. Even established HTA agencies in high-income countries have noted difficulties in recruiting and retaining specialists in fields such as health economics, real-world evidence, and patient engagement []. The consensus on this barrier shows the urgency of investing in local training and retention strategies.

Lack of Financial Resources: A persistent barrier to the institutionalization of HTA in sub-Saharan Africa is the absence of stable financial commitments from national governments. Evidence from Ghana and Malawi highlights this challenge. Addo, et al. and Mfutso-Bengo, et al.'s study shows that limited domestic resources force a country to rely on external donors, leaving HTA vulnerable to shifting priorities []. These findings resonate with broader analyses of constrained health budgets in the region, such as Pitt, et al.’s work, which highlights the structural fiscal limitations that restrict investments in evidence-informed decision-making processes []. At the country level, Mfutso-Bengo, et al. illustrate how resource scarcity hampers Malawi’s efforts to institutionalize HTA, echoing Drummond, et al.’s observation that financial shortfalls threaten the sustainability of HTA systems more generally []. Beyond identifying the problem, Oortwijn, et al. propose that innovative financing mechanisms such as pooling resources regionally or embedding HTA into routine budget lines could help mitigate these financial constraints, a direction that aligns with recent calls for sustainable domestic funding models [].

The absence of standardized frameworks and guidelines poses a critical barrier to HTA institutionalization in sub-Saharan Africa, with direct implications for the quality and legitimacy of health policy decisions. Evidence from Malawi and Kenya shows how gaps in methodological consistency and decision-making structures constrain the ability of governments to allocate resources effectively []. This finding is in agreement with Kaló, et al. who argue that weak governance structures undermine HTA development []. The result is fragmented and ad hoc adoption of HTA, limiting its potential to improve efficiency and equity in health systems. Although Wilkinson, et al. note that global frameworks can be adapted to local contexts, the absence of such adaptations continues to restrict HTA’s policy impact in the region [].

Political interference is a persistent barrier to the adoption of HTA, both in sub-Saharan Africa and globally. In Uganda, decision-making has been shown to reflect political interests rather than evidence-informed processes []. This mirrors broader findings that political pressures frequently undermine evidence-based policymaking. Similar challenges have been reported across low- and middle-income countries, where HTA recommendations are often sidelined in favor of short-term political agendas. Globally, scholars emphasize that safeguarding HTA from such influence requires institutional mechanisms that reinforce transparency and accountability []. At the same time, strategies such as stakeholder advocacy and cultivating political will remain essential for ensuring that HTA evidence is integrated into sustainable policy decisions [].

Cultural and legal factors represent significant barriers to HTA adoption in sub-Saharan Africa. In Ghana, Addo, et al. observed that national laws and entrenched institutional cultures often deprioritize cost-effectiveness []. Cultural resistance to evidence-informed decision-making further weakens the uptake of HTA. This finding supports Kaló, et al.’s argument that governance and normative structures can undermine institutionalization []. Addressing these barriers requires structural reforms, as reported by Nemzoff, et al.'s study that legal and regulatory changes are essential to embed HTA into policymaking processes, a perspective that resonates with recent calls for more robust policy frameworks in the region [].

These findings highlight the need for multifaceted interventions, including capacity building, sustainable financing, standardized frameworks, and stakeholder engagement, to institutionalize HTA in Sub-Saharan Africa. Enablers such as international collaboration and UHC alignment offer scalable pathways, as seen in Kenya and Ethiopia. However, the studies’ focus on six countries limits generalizability, and the reliance on qualitative methodologies may introduce subjectivity. Incomplete reporting of barriers and enablers suggests potential underestimation of challenges. Future research should incorporate quantitative designs, longitudinal studies, and underrepresented countries to enhance the evidence base for HTA adoption and support equitable health financing in Sub-Saharan Africa.

This study has several limitations. First, the limited number of country-specific studies restricts the generalizability of findings across the region. Second, methodological heterogeneity, which ranges from qualitative interviews to mixed methods, makes direct comparisons of results challenging. Many studies rely heavily on stakeholder perceptions rather than robust empirical or longitudinal data, thus reducing the ability to assess the long-term effectiveness of HTA integration. Some studies lack clear reporting on sample sizes and respondent profiles, and there is also a notable absence of patient and public perspectives in the data. Furthermore, publication bias may be present, as the literature tends to emphasize countries with more visible or advanced HTA initiatives.

Policy recommendations

Downey LE, Mehndiratta A, Grover A, Gauba V, Sheikh K, Prinja S, Singh R, Cluzeau FA, Dabak S, Teerawattananon Y, Kumar S, Swaminathan S. Institutionalising health technology assessment: establishing the Medical Technology Assessment Board in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2017 Jun 26;2(2):e000259. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000259. PMID: 29225927; PMCID: PMC5717947.

Kriza C, Hanass-Hancock J, Odame EA, Deghaye N, Aman R, Wahlster P, Marin M, Gebe N, Akhwale W, Wachsmuth I, Kolominsky-Rabas PL. A systematic review of health technology assessment tools in sub-Saharan Africa: methodological issues and implications. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014 Dec 2;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-66. PMID: 25466570; PMCID: PMC4265527.

Mbau R, Vassall A, Gilson L, Barasa E. Factors influencing institutionalization of health technology assessment in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Jun 22;23(1):681. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09673-4. PMID: 37349812; PMCID: PMC10288787.

Behzadifar M, Shahabi S, Bakhtiari A, Azari S, Yarahmadi M, Martini M, Behzadifar M. Challenges in adopting health technology assessment for evidence-based policy in Iran: a qualitative study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025 Apr 23;44(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s41043-025-00887-2. PMID: 40269979; PMCID: PMC12020206.

Hollingworth S, Fenny AP, Yu SY, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K. Health technology assessment in sub-Saharan Africa: a descriptive analysis and narrative synthesis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021 Jul 7;19(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12962-021-00293-5. PMID: 34233710; PMCID: PMC8261797.

Erku D, Walker D, Caruso AA, Wubishet B, Assefa Y, Abera S, Hailu A, Scuffham P. Institutionalizing health technology assessment in Ethiopia: seizing the window of opportunity. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2023 Jul 21;39(1):e49. doi: 10.1017/S0266462323000454. PMID: 37477002; PMCID: PMC11570159.

Gautier L, Ridde V. Health financing policies in Sub-Saharan Africa: government ownership or donors' influence? A scoping review of policymaking processes. Glob Health Res Policy. 2017 Aug 8;2:23. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0043-x. PMID: 29202091; PMCID: PMC5683243.

McCollum R, Theobald S, Otiso L, Martineau T, Karuga R, Barasa E, Molyneux S, Taegtmeyer M. Priority setting for health in the context of devolution in Kenya: implications for health equity and community-based primary care. Health Policy Plan. 2018 Jul 1;33(6):729-742. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy043. PMID: 29846599; PMCID: PMC6005116.

Oortwijn WJ, Vondeling H, Bouter L. The use of societal criteria in priority setting for health technology assessment in The Netherlands. Initial experiences and future challenges. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998 Spring;14(2):226-36. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300012216. PMID: 9611899.

Barasa EW, Cleary S, Molyneux S, English M. Setting healthcare priorities: a description and evaluation of the budgeting and planning process in county hospitals in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2017 Apr 1;32(3):329-337. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw132. PMID: 27679522; PMCID: PMC5362066.

Mfutso-Bengo J, Jeremiah F, Kasende-Chinguwo F, Ng'ambi W, Nkungula N, Kazanga-Chiumia I, Juma M, Chawani M, Chinkhumba J, Twea P, Chirwa E, Langwe K, Manthalu G, Ngwira LG, Nkhoma D, Colbourn T, Revill P, Sculpher M. A qualitative study on the feasibility and acceptability of institutionalizing health technology assessment in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Apr 11;23(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09276-z. PMID: 37041590; PMCID: PMC10088659.

Uzochukwu BSC, Okeke C, O'Brien N, Ruiz F, Sombie I, Hollingworth S. Health technology assessment and priority setting for universal health coverage: a qualitative study of stakeholders' capacity, needs, policy areas of demand and perspectives in Nigeria. Global Health. 2020 Jul 8;16(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00583-2. PMID: 32641066; PMCID: PMC7346669.

Kim T, Sharma M, Teerawattananon Y, Oh C, Ong L, Hangoma P, Adhikari D, Pempa P, Kairu A, Orangi S, Dabak SV. Addressing Challenges in Health Technology Assessment Institutionalization for Furtherance of Universal Health Coverage Through South-South Knowledge Exchange: Lessons From Bhutan, Kenya, Thailand, and Zambia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021 May;24:187-192. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.12.011. Epub 2021 Apr 7. PMID: 33838558; PMCID: PMC8163602.

Surgey G, Chalkidou K, Reuben W, Suleman F, Miot J, Hofman K. Introducing health technology assessment in Tanzania. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020 Apr;36(2):80-86. doi: 10.1017/S0266462319000588. Epub 2019 Aug 12. PMID: 31402790.

Addo R, Hall J, Haas M, Goodall S. The knowledge and attitude of Ghanaian decision-makers and researchers towards health technology assessment. Soc Sci Med. 2020 Apr;250:112889. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112889. Epub 2020 Feb 29. PMID: 32146238.

Mayora C, Kazibwe J, Ssempala R, Nakimuli B, Ssennyonjo A, Ekirapa E, Byakika S, Aliti T, Musila T, Gad M, Vassall A, Ruiz F, Ssengooba F. Health technology assessment (HTA) readiness in Uganda: stakeholder's perceptions on the potential application of HTA to support national universal health coverage efforts. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2023 Oct 31;39(1):e65. doi: 10.1017/S0266462323002635. PMID: 37905441; PMCID: PMC11579667.

Kaló Z, Gheorghe A, Huic M, Csanádi M, Kristensen FB. HTA Implementation Roadmap in Central and Eastern European Countries. Health Econ. 2016 Feb;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):179-92. doi: 10.1002/hec.3298. Epub 2016 Jan 14. PMID: 26763688; PMCID: PMC5066682.

Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Marten R, Vega J, Teerawattananon Y, Tritasavit N, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Seiter A, Kieny MP, Hofman K, Culyer AJ. Priority-setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Jun 1;94(6):462-7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.155721. Epub 2016 Feb 12. PMID: 27274598; PMCID: PMC4890204.

Wilkinson T, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Revill P, Briggs A, Cairns JA, Teerawattananon Y, Asfaw E, Lopert R, Culyer AJ, Walker DG. The International Decision Support Initiative Reference Case for Economic Evaluation: An Aid to Thought. Value Health. 2016 Dec;19(8):921-928. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.015. PMID: 27987641.

Drummond MF, Augustovski F, Bhattacharyya D, Campbell J, Chaiyakunapruk N, Chen Y, Galindo-Suarez RM, Guerino J, Mejía A, Mujoomdar M, Ollendorf D, Ronquest N, Torbica A, Tsiao E, Watkins J, Yeung K; ISPOR HTA Council Working Group on HTA in Pluralistic Healthcare Systems collaborators. Challenges of Health Technology Assessment in Pluralistic Healthcare Systems: An ISPOR Council Report. Value Health. 2022 Aug;25(8):1257-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.02.006. Erratum in: Value Health. 2023 Dec;26(12):1811. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2023.06.010. PMID: 35931428.

MacQuilkan K, Baker P, Downey L, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, Prinja S, Zhao K, Wilkinson T, Glassman A, Hofman K. Strengthening health technology assessment systems in the global south: a comparative analysis of the HTA journeys of China, India and South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1527556. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1527556. PMID: 30326795; PMCID: PMC6197020.

Pitt C, Vassall A, Teerawattananon Y, Griffiths UK, Guinness L, Walker D, Foster N, Hanson K. Foreword: Health Economic Evaluations in Low- and Middle-income Countries: Methodological Issues and Challenges for Priority Setting. Health Econ. 2016 Feb;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):1-5. doi: 10.1002/hec.3319. PMID: 26804357; PMCID: PMC5066637.

Filby A, McConville F, Portela A. What Prevents Quality Midwifery Care? A Systematic Mapping of Barriers in Low and Middle Income Countries from the Provider Perspective. PLoS One. 2016 May 2;11(5):e0153391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153391. PMID: 27135248; PMCID: PMC4852911.

Oortwijn W, Sampietro-Colom L, Habens F, Trowman R. HOW CAN HEALTH SYSTEMS PREPARE FOR NEW AND EMERGING HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES? THE ROLE OF HORIZON SCANNING REVISITED. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018 Jan;34(3):254-259. doi: 10.1017/S0266462318000363. Epub 2018 Jun 11. PMID: 29888687.

Nemzoff C, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, Mehndiratta A, Guinness L, Cluzeau F, Shah H. Adaptive health technology assessment to facilitate priority setting in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Apr;6(4):e004549. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004549. PMID: 33903175; PMCID: PMC8076924.

Orem JN, Mafigiri DK, Nabudere H, Criel B. Improving knowledge translation in Uganda: more needs to be done. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 Jan 18;17 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):14. doi: 10.11694/pamj.supp.2014.17.1.3482. PMID: 24624247; PMCID: PMC3946259.

Wanjiku CK. Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in Sub-Saharan Africa Health Financing Decisions Systematic Review. IgMin Res. August 27, 2025; 3(8): 335-342. IgMin ID: igmin314; DOI:10.61927/igmin314; Available at: igmin.link/p314

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Department of Health Management and Informatics, Kenyatta University, Kenya

Address Correspondence:

Charles Karanja Wanjiku, Department of Health Management and Informatics, Kenyatta University, Kenya, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Wanjiku CK. Barriers and Enablers to the Adoption of Health Technology Assessment (HTA) in Sub-Saharan Africa Health Financing Decisions Systematic Review. IgMin Res. August 27, 2025; 3(8): 335-342. IgMin ID: igmin314; DOI:10.61927/igmin314; Available at: igmin.link/p314

Copyright: © 2025 Wanjiku CK This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the search strategy and selection ...

Figure 1: Flow diagram of the search strategy and selection ...

Table 1: Scoring template for the selected study articles....

Table 1: Scoring template for the selected study articles....

Table 2: Characteristics of the studies selected for data a...

Table 2: Characteristics of the studies selected for data a...

Table 3: Continuing, Knowledge synthesis of selected studie...

Table 3: Continuing, Knowledge synthesis of selected studie...

Downey LE, Mehndiratta A, Grover A, Gauba V, Sheikh K, Prinja S, Singh R, Cluzeau FA, Dabak S, Teerawattananon Y, Kumar S, Swaminathan S. Institutionalising health technology assessment: establishing the Medical Technology Assessment Board in India. BMJ Glob Health. 2017 Jun 26;2(2):e000259. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000259. PMID: 29225927; PMCID: PMC5717947.

Kriza C, Hanass-Hancock J, Odame EA, Deghaye N, Aman R, Wahlster P, Marin M, Gebe N, Akhwale W, Wachsmuth I, Kolominsky-Rabas PL. A systematic review of health technology assessment tools in sub-Saharan Africa: methodological issues and implications. Health Res Policy Syst. 2014 Dec 2;12:66. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-12-66. PMID: 25466570; PMCID: PMC4265527.

Mbau R, Vassall A, Gilson L, Barasa E. Factors influencing institutionalization of health technology assessment in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Jun 22;23(1):681. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09673-4. PMID: 37349812; PMCID: PMC10288787.

Behzadifar M, Shahabi S, Bakhtiari A, Azari S, Yarahmadi M, Martini M, Behzadifar M. Challenges in adopting health technology assessment for evidence-based policy in Iran: a qualitative study. J Health Popul Nutr. 2025 Apr 23;44(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s41043-025-00887-2. PMID: 40269979; PMCID: PMC12020206.

Hollingworth S, Fenny AP, Yu SY, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K. Health technology assessment in sub-Saharan Africa: a descriptive analysis and narrative synthesis. Cost Eff Resour Alloc. 2021 Jul 7;19(1):39. doi: 10.1186/s12962-021-00293-5. PMID: 34233710; PMCID: PMC8261797.

Erku D, Walker D, Caruso AA, Wubishet B, Assefa Y, Abera S, Hailu A, Scuffham P. Institutionalizing health technology assessment in Ethiopia: seizing the window of opportunity. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2023 Jul 21;39(1):e49. doi: 10.1017/S0266462323000454. PMID: 37477002; PMCID: PMC11570159.

Gautier L, Ridde V. Health financing policies in Sub-Saharan Africa: government ownership or donors' influence? A scoping review of policymaking processes. Glob Health Res Policy. 2017 Aug 8;2:23. doi: 10.1186/s41256-017-0043-x. PMID: 29202091; PMCID: PMC5683243.

McCollum R, Theobald S, Otiso L, Martineau T, Karuga R, Barasa E, Molyneux S, Taegtmeyer M. Priority setting for health in the context of devolution in Kenya: implications for health equity and community-based primary care. Health Policy Plan. 2018 Jul 1;33(6):729-742. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czy043. PMID: 29846599; PMCID: PMC6005116.

Oortwijn WJ, Vondeling H, Bouter L. The use of societal criteria in priority setting for health technology assessment in The Netherlands. Initial experiences and future challenges. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998 Spring;14(2):226-36. doi: 10.1017/s0266462300012216. PMID: 9611899.

Barasa EW, Cleary S, Molyneux S, English M. Setting healthcare priorities: a description and evaluation of the budgeting and planning process in county hospitals in Kenya. Health Policy Plan. 2017 Apr 1;32(3):329-337. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw132. PMID: 27679522; PMCID: PMC5362066.

Mfutso-Bengo J, Jeremiah F, Kasende-Chinguwo F, Ng'ambi W, Nkungula N, Kazanga-Chiumia I, Juma M, Chawani M, Chinkhumba J, Twea P, Chirwa E, Langwe K, Manthalu G, Ngwira LG, Nkhoma D, Colbourn T, Revill P, Sculpher M. A qualitative study on the feasibility and acceptability of institutionalizing health technology assessment in Malawi. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023 Apr 11;23(1):353. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-09276-z. PMID: 37041590; PMCID: PMC10088659.

Uzochukwu BSC, Okeke C, O'Brien N, Ruiz F, Sombie I, Hollingworth S. Health technology assessment and priority setting for universal health coverage: a qualitative study of stakeholders' capacity, needs, policy areas of demand and perspectives in Nigeria. Global Health. 2020 Jul 8;16(1):58. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00583-2. PMID: 32641066; PMCID: PMC7346669.

Kim T, Sharma M, Teerawattananon Y, Oh C, Ong L, Hangoma P, Adhikari D, Pempa P, Kairu A, Orangi S, Dabak SV. Addressing Challenges in Health Technology Assessment Institutionalization for Furtherance of Universal Health Coverage Through South-South Knowledge Exchange: Lessons From Bhutan, Kenya, Thailand, and Zambia. Value Health Reg Issues. 2021 May;24:187-192. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2020.12.011. Epub 2021 Apr 7. PMID: 33838558; PMCID: PMC8163602.

Surgey G, Chalkidou K, Reuben W, Suleman F, Miot J, Hofman K. Introducing health technology assessment in Tanzania. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2020 Apr;36(2):80-86. doi: 10.1017/S0266462319000588. Epub 2019 Aug 12. PMID: 31402790.

Addo R, Hall J, Haas M, Goodall S. The knowledge and attitude of Ghanaian decision-makers and researchers towards health technology assessment. Soc Sci Med. 2020 Apr;250:112889. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112889. Epub 2020 Feb 29. PMID: 32146238.

Mayora C, Kazibwe J, Ssempala R, Nakimuli B, Ssennyonjo A, Ekirapa E, Byakika S, Aliti T, Musila T, Gad M, Vassall A, Ruiz F, Ssengooba F. Health technology assessment (HTA) readiness in Uganda: stakeholder's perceptions on the potential application of HTA to support national universal health coverage efforts. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2023 Oct 31;39(1):e65. doi: 10.1017/S0266462323002635. PMID: 37905441; PMCID: PMC11579667.

Kaló Z, Gheorghe A, Huic M, Csanádi M, Kristensen FB. HTA Implementation Roadmap in Central and Eastern European Countries. Health Econ. 2016 Feb;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):179-92. doi: 10.1002/hec.3298. Epub 2016 Jan 14. PMID: 26763688; PMCID: PMC5066682.

Chalkidou K, Glassman A, Marten R, Vega J, Teerawattananon Y, Tritasavit N, Gyansa-Lutterodt M, Seiter A, Kieny MP, Hofman K, Culyer AJ. Priority-setting for achieving universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2016 Jun 1;94(6):462-7. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.155721. Epub 2016 Feb 12. PMID: 27274598; PMCID: PMC4890204.

Wilkinson T, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, Revill P, Briggs A, Cairns JA, Teerawattananon Y, Asfaw E, Lopert R, Culyer AJ, Walker DG. The International Decision Support Initiative Reference Case for Economic Evaluation: An Aid to Thought. Value Health. 2016 Dec;19(8):921-928. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.015. PMID: 27987641.

Drummond MF, Augustovski F, Bhattacharyya D, Campbell J, Chaiyakunapruk N, Chen Y, Galindo-Suarez RM, Guerino J, Mejía A, Mujoomdar M, Ollendorf D, Ronquest N, Torbica A, Tsiao E, Watkins J, Yeung K; ISPOR HTA Council Working Group on HTA in Pluralistic Healthcare Systems collaborators. Challenges of Health Technology Assessment in Pluralistic Healthcare Systems: An ISPOR Council Report. Value Health. 2022 Aug;25(8):1257-1267. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2022.02.006. Erratum in: Value Health. 2023 Dec;26(12):1811. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2023.06.010. PMID: 35931428.

MacQuilkan K, Baker P, Downey L, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, Prinja S, Zhao K, Wilkinson T, Glassman A, Hofman K. Strengthening health technology assessment systems in the global south: a comparative analysis of the HTA journeys of China, India and South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2018;11(1):1527556. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1527556. PMID: 30326795; PMCID: PMC6197020.

Pitt C, Vassall A, Teerawattananon Y, Griffiths UK, Guinness L, Walker D, Foster N, Hanson K. Foreword: Health Economic Evaluations in Low- and Middle-income Countries: Methodological Issues and Challenges for Priority Setting. Health Econ. 2016 Feb;25 Suppl 1(Suppl Suppl 1):1-5. doi: 10.1002/hec.3319. PMID: 26804357; PMCID: PMC5066637.

Filby A, McConville F, Portela A. What Prevents Quality Midwifery Care? A Systematic Mapping of Barriers in Low and Middle Income Countries from the Provider Perspective. PLoS One. 2016 May 2;11(5):e0153391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0153391. PMID: 27135248; PMCID: PMC4852911.

Oortwijn W, Sampietro-Colom L, Habens F, Trowman R. HOW CAN HEALTH SYSTEMS PREPARE FOR NEW AND EMERGING HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES? THE ROLE OF HORIZON SCANNING REVISITED. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2018 Jan;34(3):254-259. doi: 10.1017/S0266462318000363. Epub 2018 Jun 11. PMID: 29888687.

Nemzoff C, Ruiz F, Chalkidou K, Mehndiratta A, Guinness L, Cluzeau F, Shah H. Adaptive health technology assessment to facilitate priority setting in low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021 Apr;6(4):e004549. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004549. PMID: 33903175; PMCID: PMC8076924.

Orem JN, Mafigiri DK, Nabudere H, Criel B. Improving knowledge translation in Uganda: more needs to be done. Pan Afr Med J. 2014 Jan 18;17 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):14. doi: 10.11694/pamj.supp.2014.17.1.3482. PMID: 24624247; PMCID: PMC3946259.