A Model of the Enforcement of Laws in Tramadol Drug Abusers

MathematicsReceived 26 Dec 2025 Accepted 07 Jan 2026 Published online 08 Jan 2026

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Next Full Text

Detection of Adenoviruses and Astroviruses in Patients and Marine Animals in the Republic of Guinea

Previous Full Text

Soil Water Vegetation Carrying Capacity and Quality Agricultural Produce

Received 26 Dec 2025 Accepted 07 Jan 2026 Published online 08 Jan 2026

Tramadol initially use as an analgesic which lead to addiction and overdose worldwide due to prolong consumption, particularly in low and middle income countries. This paper deals with a mathematical approach of Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model (MRTAM) to analyze affected population with time domain. This model is a non-linear compartmental framework, which simulates the abuse progression. Parameters such as prevention rate (s), relapse rate (σ2), treatment rate (ξ1), and law enforcement (ξ) influence the abuse population and the reproduction number (R0). Eigenvalues of the dynamics are derived to analyze the stability and behavior of the system. Results show that the system is highly sensitive to prescription inflow, progression and prevention parameters. Endemic equilibrium is obtained and also presented the analysis of bifurcation and partial rank correlation coefficient (PRCC) to quantify and assess the influence of various parameters on the abuse population.

MSC Classification: 92C60; 92D25

The use of tramadol and other synthetic opioids for pain management and the resulting prevalence are well known. These drugs initially introduced as a centrally acting analgesic for moderately severe pain and it was considered to have a lower potential for dependence compared to traditional opioids such as codeine and heroin. However, clinical and epidemiological evidences showed that it could cause addiction, dependence and even withdrawal symptoms due to prolong use. A significant progress has been achieved with the use of mathematical model in the infectious diseases, ecosystems and the dynamics of substance abuse.

An abuser is defined as an individual who is habitual or dependent to drug resulting in harm to physical and psychological heath with social relationships or negative impacts to the community. In many developing nations, particularly across the Africa and Asia, tramadol was originally perceived as a safer option against other drugs due to low side effects. It has been observed that over the past decades, there has been a steady increased in misuse, dependence and illegal trafficking of tramadol (Figure 1).

Surveillance and treatment data indicates that the number of individuals entering rehabilitation programs have increased. The rate of admissions of tramadol abusers at initial stages has declined not only due to social exposure and accessibility but also by the effectiveness of regulatory and enforcement mechanisms. The quantification of weak or delayed enforcement responses, including insufficient monitoring pharmaceutical distributions and prevention of illegal trafficking, regulatory efficiency, and public health measures have been observed to influence the persistence of addiction within the population.

Caldwell, et al. [1] demonstrated that relying solely on rehabilitation and other treatment programs is not enough to combat the Vicodin abusers in the United States. They developed the Multiple Relapse Vicodin Abuse (MRVA) model and simulated over 250 months with initial population of 2 million abusers to reach a steady state after 150 months. The epidemic threshold value (R0) for the drug heroin abusers are discussed using the sensitivity analysis, backward bifurcation and endemic equilibria [2]. Hogea, et al. [3] studied how non linear reaction-diffusion dynamics can capture the evolution of complex biological systems. Mandal, et al. [4] studied the mathematical model on the impact of awareness among human on reduction of environmental toxins affecting planktonic system. Nazmul and Pal [5] found that disease can be eradicated from the system by controlling the value of basic reproduction number less than one. World Drug Report 2024 [6] due to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reported the rise in drug user due to the supply and demand of synthetic opioids leading to disorders and environmental harms. World Health Organisation (WHO) revealed the role of tramadol in the use of poly-substances [7,8] which increase the euphoric and sedative effects with epidemiological data showing that tramadol is among the most frequently diverted drugs sought for non-medical use specifically through intentional intake.

In India, pharmaceutical opioids were found to constitute a significant portion in the opioid crisis [9] with user rate of 0.96% in the age group of 10 - 75 years. Walwyn, et al. [10] highlighted that the optimization of current opioid subscriptions must be focused on enhancing clinical awareness to reduce the diversion from medical use. Befekadu and Zhu [11] developed an opioid endemic model and analyzed how random fluctuations in susceptibility can influence epidemic trajectories and control strategies.Nielsen, et al. [12] reviewed commonly described approaches for managing codeine dependence including opioid taper, opioid agonist treatment and psychological therapies. Mukherjee, et al. [13] investigated the tapentadol abuse and dependence in India and concluded that the tapentadol had received more online interest than Ilaprazole and parallel in temporal and spatial trends with Tramadol. Nyabadza, et al. [14,15] theoretically modeled the drug abuse and related crimes in the Western Cape, South Africa and highlighted the usefulness of mathematical modeling to combat abuser and its related problems. The dynamics of spread of crime in a society was modeled [16-18] and the basic reproduction number R0 is computed for all possible equilibria. It is observed that the crime/substance free equilibrium is globally asymptotically stable when R0 < 1 while the entrenched equilibria become stable when R0 > 1 [19]. An algorithm called "Abuse Index" was developed [20] and a comparison has been made to know rate of abusers after 12 months of prescriptions of tramadol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and hydrocodone to the patients with chronic non-cancer pain (CNP). It is very common that the drug abusers commit crimes [21,22] and governments have been implementing different policies in the form of rules and regulations [23-26]. Muli [27] designed a mathematical model incorporating the impact of policing and rehabilitation on the proliferation of drug and substance abuse in the community. Mamo, et al. [28] explored the dynamics of crime and substance abuse within a population by developing a novel mathematical model that integrates social interactions, rehabilitation efforts and relapse probabilities. Mikhaylov, et al. [29] recommended an integrated decision system using iteration enhanced collaborative filtering and golden cut bipolar for analyzing the risk based oil market spillovers. Irshad, et al. [30] evaluated the performance of a PV / biomass hybrid renewable energy system that incorporates three distinct biomass processes, including pyrolysis, direct combustion and gasification.

A nation wide diversion survey was carried out [31] in 50 states of United States during 2002-2004 and found that the diversion of Ultram (Tramadol HCl) was low and not considered as a problem. Physical dependence on Ultram (Tramadol HCl) with both opiod-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms was explored [32-35] and recorded the withdrawal symptoms of either types was one of the more prevalent adverse events found associated with chronic drug users. However, a study conducted by Sarkar, et al. [34] in 2012 reported seven severe tramadol dependence cases stressing the need for caution while prescribing tramadol to patients and regulating its distribution. In clinical practice, observations had been made of different dosages of tramadol to examine the dependence potential of Tramadol in association with analgesic treatment [35-39].

The Government of India acknowledges that Tramadol addiction in particular is rising among the Indian population leading the authorities to monitor tramadol sales to detect drug trafficking networks [40,41]. The Prevention of Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act, 1988 (PITNDPS Act) was also implemented to monitor trafficking across India and improve enforcement capabilities in dealing with the supply of drugs.

The study reveals the dynamics of tramadol misuse and the effects of law enforcement and relapse parameters on the addicted population have been investigated. The expressions for endemic equilibrium and reproduction number are derived and shown graphically. Analytical and numerical results are presented to observe the stability of equilibrium points, bifurcation behavior, Time-domain and Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC). We have identified the key parameters that control the spread and persistence of addiction for government and public health organizations to implement proper policies and measures.

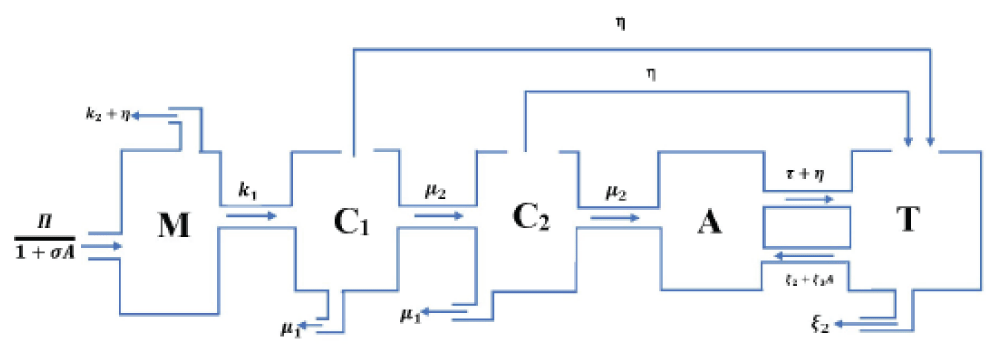

The Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model (MRTAM) is a non-linear, compartmental model specifically developed to simulate the dynamics of Tramadol abuse, misuse, addiction, recovery and relapse within a defined population over time. The model divides the total population into five key compartments as shown in Figure 2, each representing a specific group of individuals at different stages within the Tramadol abuse cycle capturing the dynamical transitions that occur between compartments due to various biological, social and behavioural factors in addiction and recovery processes. Simulations have been performed on the model using data-driven parameter values to estimate the persistence of Tramadol dependence.

The following compartments comprise in the MRTAM:

The various parameters representing the transition rates between compartments are given Table 1.

| Opinions and perspectives: Values of relevant parameters. | ||

| Symbol | Description | Typical Range |

| ? | New prescriptions | 1.5 --2.5 million |

| s | Awareness rate | [10-6,5 × 10-6] |

| ?1 | Acute to chronic progression | [0.1 --0.3] month-1 |

| ?2 | Acute cessation rate | [0.3 --0.6] month-1 |

| µ1 | Chronic cessation rate | [0.05 --0.15] month-1 |

| µ2 | Chronic abuse progression | [0.02 --0.1] month-1 |

| t | Treatment-seeking rate | [0.01 --0.05] month-1 |

| ?1 | Successful treatment rate | [0.1 --0.3] month-1 |

| ?2 | Relapse rate from treatment | [0.01 --0.3] month-1 |

| ?3 | Social relapse rate | [0.01 --0.3] people-1 month-1 |

| ? | Law enforcement rate | [0.05 -0.1] |

The model is defined by the following system of non-linear Ordinary differential equations which describe the dynamics among the five compartments

(1)

(2)

(3)

(4)

(5)

It is noted that Equation (1) represents the inflow of new prescriptions and transition from acute use to chronic use or cessation, Eqs. (2) and (3) describe the progression through chronic stages, Eq. (4) gives the transitions into abuse and relapse from treatment and Equation (5) captures the entry into treatment and outcomes including relapse and recovery. The term, reflects the reduced prescription rates due to increased public awareness and the enforcement parameter, ? have its affects as multiple transitions, simulating government or policy-driven interventions.

Equilibrium points are also known as known as steady states and it represents the condition where the populations in each compartment of the MRTAM model remain constant over time. The positive steady state of the model is represented by E* which signifies a state, where there is a stable and represent positive number of individuals in each compartments, including those engaged in tramadol abuse. It is determined by setting zeroes for all derivatives as

(6)

where ( ) represents the equilibrium position of the model. Solving these equations (1)-(6) yield the steady-state populations in each compartment as

(7)

(8)

(9)

(10)

Thus, the endemic equilibrium, E* is given by

(11)

The basic reproduction number, R0 reflects the average number of new abusers generated by a single individual in a completely susceptible population. We adapt R0 to incorporate law enforcement as

(12)

where ? is new users via prescriptions, s is prevention via awareness, ?1 and ?2 are transition from acute to chronic and cessation, µ2 is the transition to abuse, µ1 is chronic cessation, ?1 is the treatment success rate, and ? is the effect of law enforcement. It is observed that increasing ? lowers R0 by accelerating removal from abuse states. When R0 < 1, the system stabilizes, and tramadol abuse declines. When R0 > 1, the epidemic can persist or worsen. Effective interventions should thus aim to reduce R0 below 1.

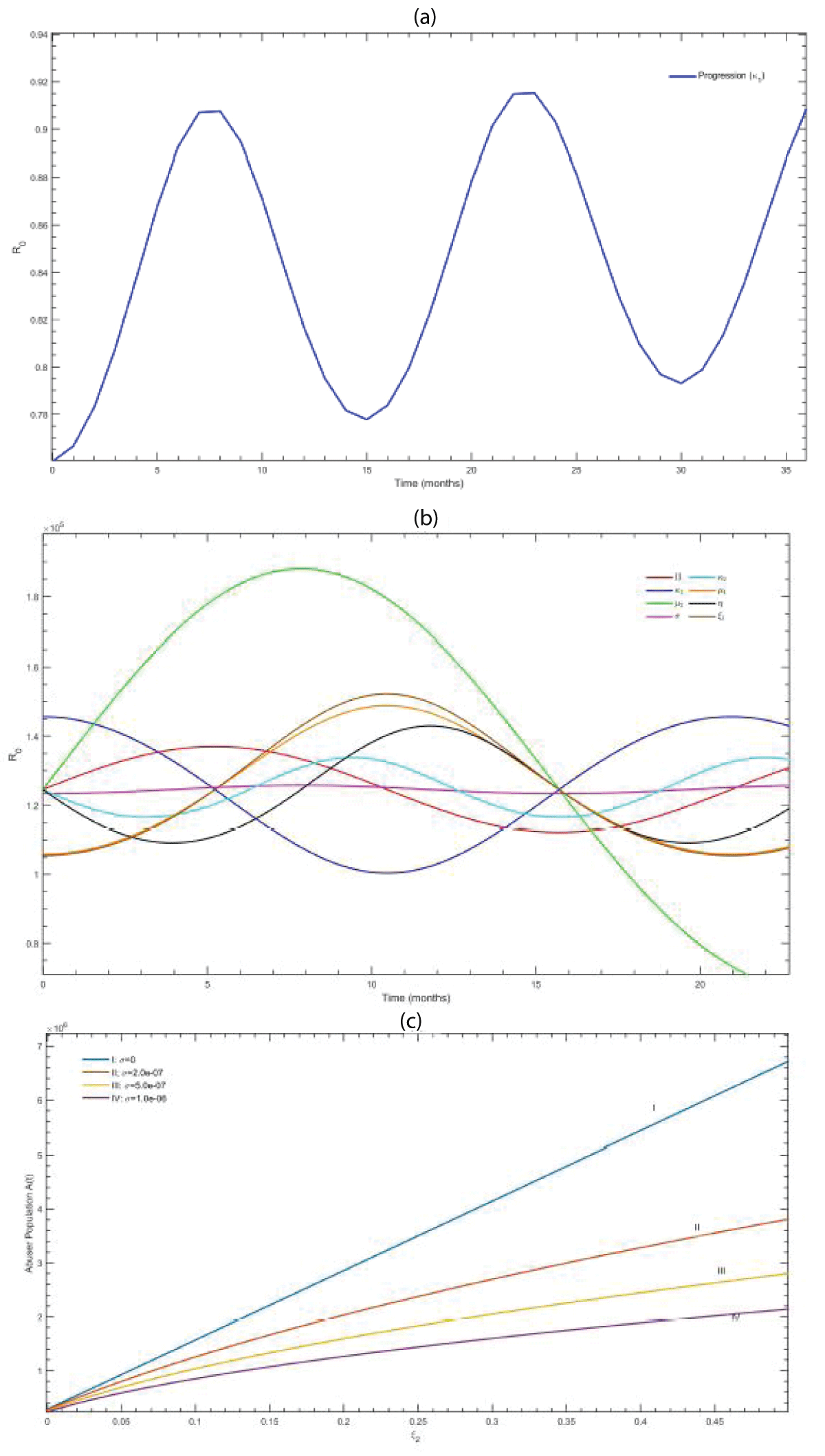

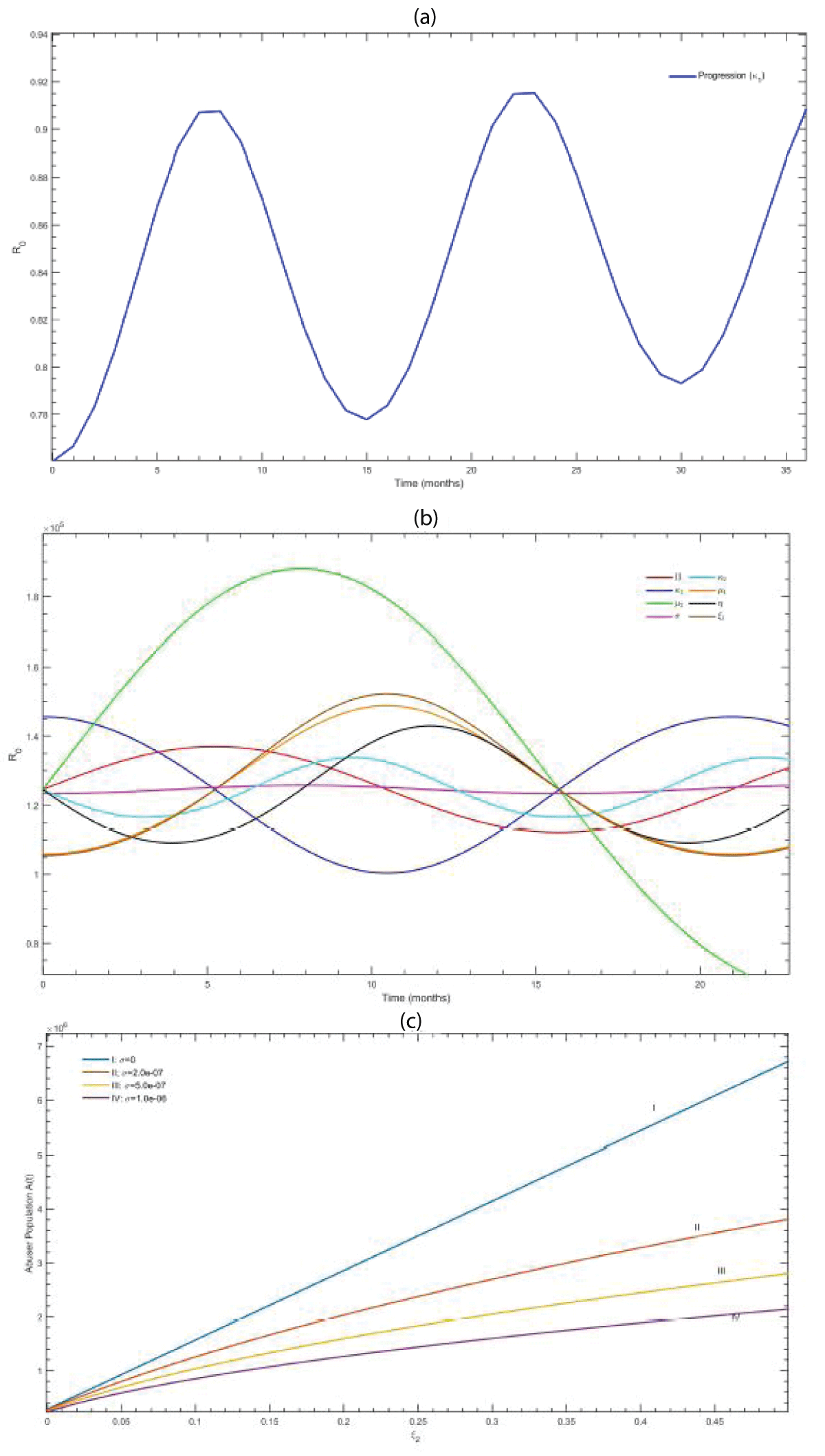

The reproduction numbers, R0, are calculated and shown in Figure 3 over the span of 24-36 months under varying system parameters to investigate the dynamics and the sensitivity of the abuse population to certain parameters, such as treatment rates and awareness interventions. In Figure 3(a), the analysis measured the sensitivity of R0 with respect to the acute progression parameter ?1 over 36 months. It is observed that ?1 oscillates at moderate amplitude with periodic fluctuations. The results demonstrated that R0 is positively sensitive to ?1 at early intervals, suggesting that policy measures aimed at reducing progression during the initial months of exposure will be particularly effective in suppressing the abuse potential. In Figure 3(b), we acknowledge that high awareness reduces equilibrium abuse levels and accelerates the convergence towards a converging equilibrium. In all cases, the abuse compartment stabilized within 250 months, but the equilibrium level A* showed dependence on awareness intensity. For s = 0, the abuser population stabilized above 6.5 × 105, whereas an awareness rate of s = 1.0 × 10-6 suppressed the population to below 1.5 × 105. The decrease in equilibrium reflects the impact of awareness programs as a non-pharmaceutical intervention. We have observed in Figure 3(c) that there were oscillations in the prescription flow (?), acute progression (?1), transition rate from chronic to abuse (µ2), cessation rates (?2 and µ1), treatment success (?1), and intensity of law enforcement (?) parameters, indicating significant influence on R0. Among these, fluctuations in ? and ?1 produced the strongest variations in R0, showing the risk of the system’s stability to changes in prescription practices and the acute-to-chronic transition pathway. In contrast, variations in µ1 and s produced comparatively mild changes, indicating less direct influence on the reproduction potential of abuse.

Figure 3: (a) Effect of awareness rate (s) on the abuse population A(t), (b) Sensitivity analysis of the basic reproduction number(R0) with respect to the progression rate, ?1, (c) Temporal variation of the basic reproduction number(R0) under various parameters.

Figure 3: (a) Effect of awareness rate (s) on the abuse population A(t), (b) Sensitivity analysis of the basic reproduction number(R0) with respect to the progression rate, ?1, (c) Temporal variation of the basic reproduction number(R0) under various parameters.The simulations investigated the long-term progressions of the abuser population, A(t), under different awareness rates (s). The analysis indicate that R0 is highly sensitive to prescription inflow, acute progression, and law enforcement, while the abuser equilibrium is most affected by awareness-based interventions. This emphasizes the need to include medical regulation, awareness campaigns, and early-stage progression control into a stronger intervention.

For the MRTAM, eigenvalues (?) are obtained from the characteristic polynomial of the Jacobian matrix, J at the endemic equilibrium.

(13)

(14)

where

The expressions of M11 and M14 are given by

The characteristic polynomial of the matrix is given by

We have computed the eigenvalues by taking the relevant values of parameters, in the Indian context, in Table 2. These eigenvalues are given by

| Table 2: Relevance parameters. | |

| Parameter | Value |

| ?1 | 0.2 |

| ?2 | 0.4 |

| µ1 | 0.1 |

| µ2 | 0.05 |

| t | 0.1 |

| ?1 | 0.2 |

| ? | 0.075 |

We observed that all the eigenvalues are real and negative, implying the absence of oscillations near equilibrium, that is, any disturbances away from the equilibrium will eventually decay and the system will return to its steady state. The presence of eigenvalue -0.621 twice suggests that two variables decrease at the same exponential rate. The eigenvalue -0.049, nearer to zero, indicates that the system took a long time to stabilize, causing a long transitional period.

Further to analyze the behavior and stability of the system over longer durations, stability analysis is performed at steady state equilibrium. The system of differential equations are solved using MATLAB with the initial conditions as

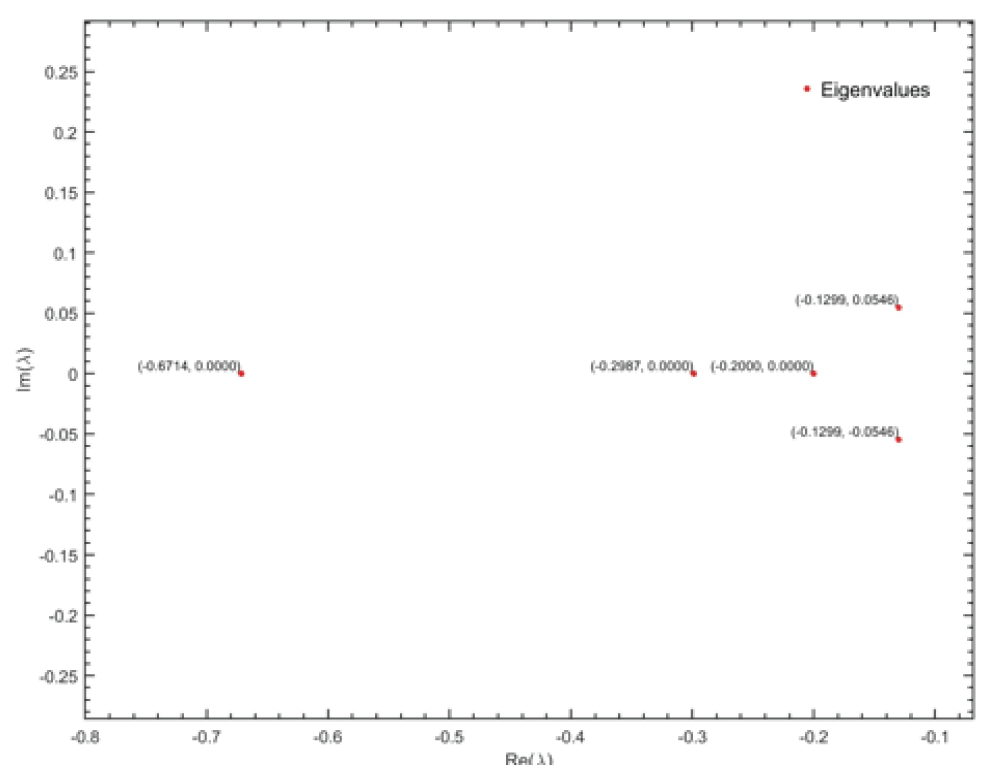

and a time period of [0,300] months to reach stable equilibrium (y*) in Figure 4. The local stability of the equilibrium has been evaluated by computing the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix (J) at y*, using the numerical differentiation method. The resulting eigenvalues were found to be

for which the graphical representation of these eigenvalues is the complex plane. In Figure 4, we observe that all the eigenvalues lie in the left half of the complex plane with the real part always negative, satisfying the necessary condition of stability and therefore the equilibrium point is a stable node.

This indicates that the system is locally stable and following some small perturbations it returns to the equilibrium state. The presence of the complex conjugate -0.1299 ± 0.0546i eigenvalues further signifies that the system's return to equilibrium is characterized by damped oscillations, as the imaginary part is responsible for the oscillatory behavior of the system while the negative real parts ensure that these oscillations decay with time, preventing any long-term prevalence.

Time domain simulation are performed over t = 36 months using MATLAB's inbuilt function with the base parameters:

and initial conditions:

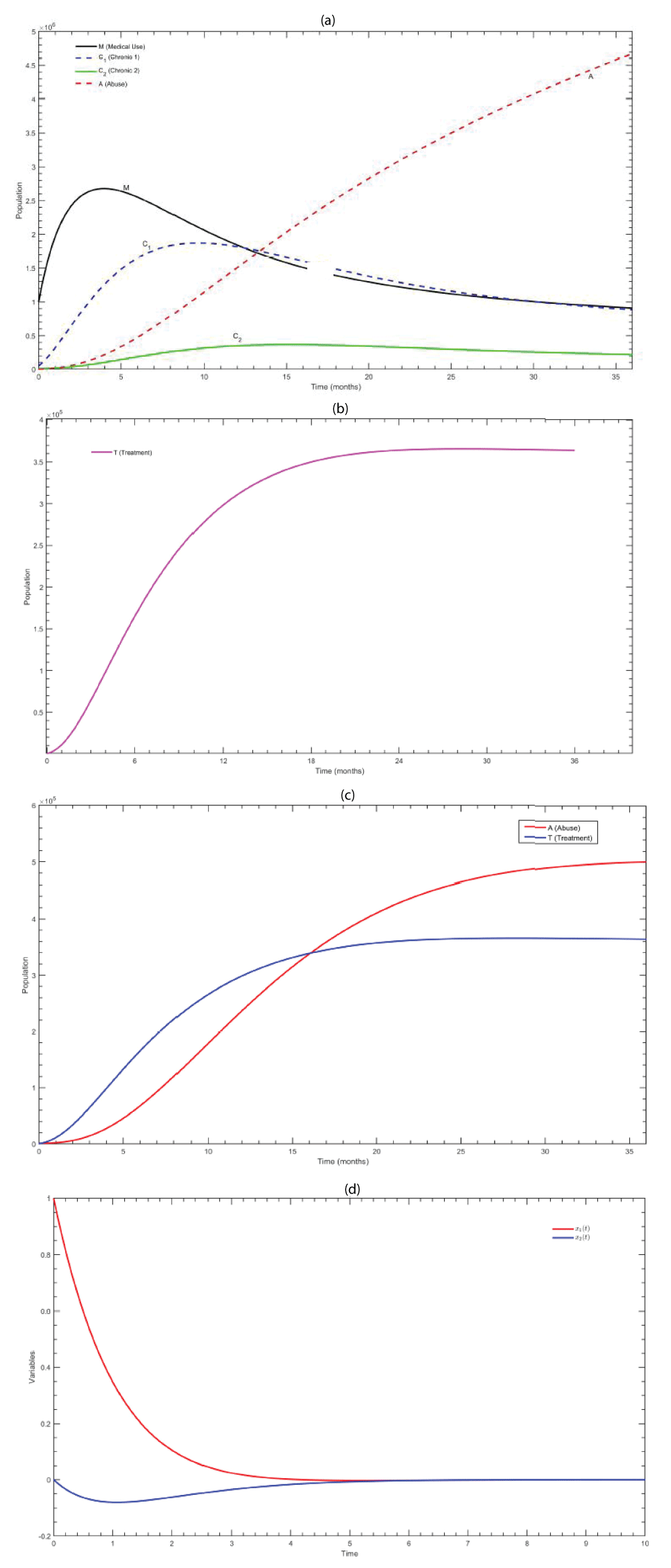

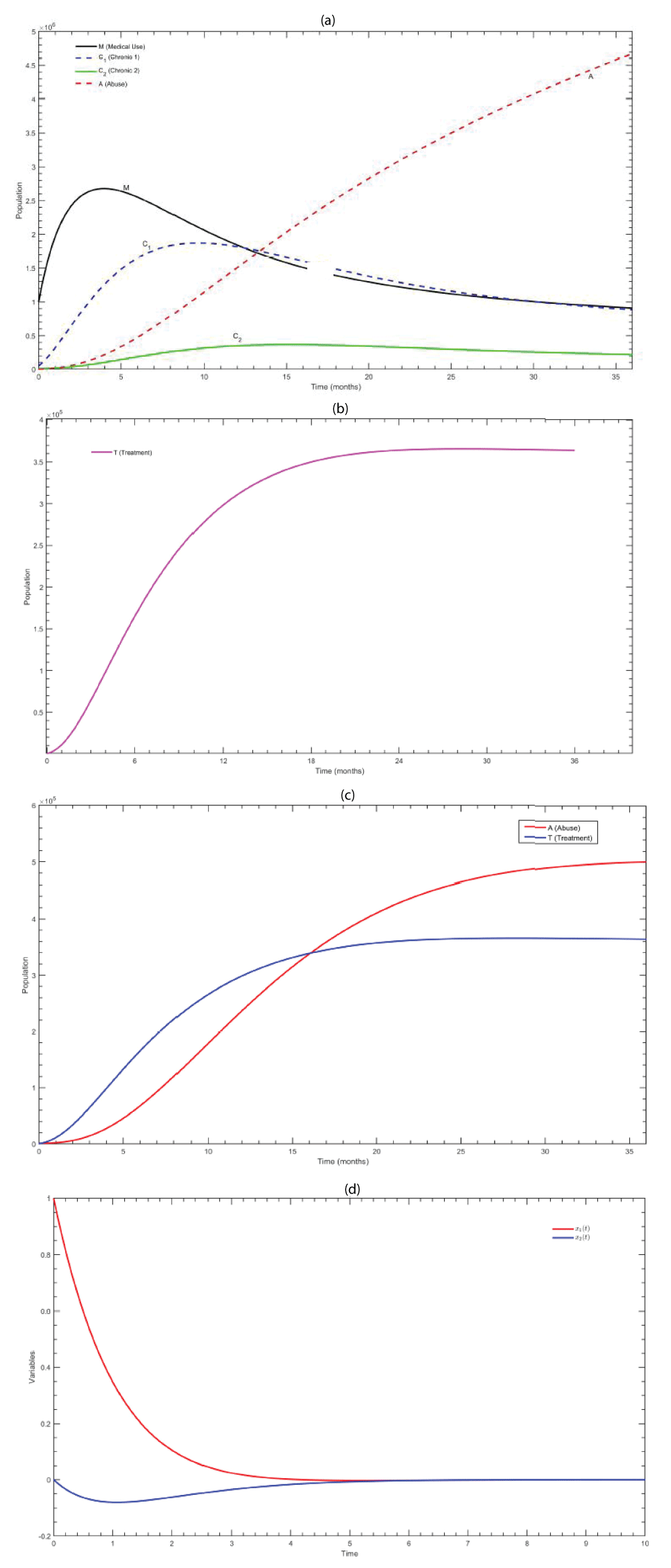

In Figure 5(a), the simulation trajectories indicate that individuals redistribute among the five compartments. The medical use compartment (M) exhibits a gradual decline from 106, explaining the balance between the inflow of prescriptions, cessation rates, and law enforcement. The early chronic compartment C1 shows an initial increase and further declines as individuals transition into late chronic use or exit via cessation and enforcement interventions, in contrast to the late chronic compartment C2, which experiences a delayed transition to reach the equilibrium. The abuse population A(t), starting from a moderate initial level of 103, increases steadily over time t. Progression rates from C2 to treatment followed by relapse ?2 rates are found to be the primary factors leading to a shifted course as it moves towards stable equilibrium A*. Hence, planned reinforcement like increase in treatment seeking and success (t, ?1), a reduction in relapses (?2, ?3), and strengthening law enforcement (?) are concluded to be critical for better outcomes.

In Figure 5(b-c), the treatment population is examined over t = 36 months to assess transitions into and out of care. The system starts with an initial population of T(0) = 500, indicating that only a small fraction of individuals enter treatment. The population initially increases as the individuals move from the abuse compartment (A) into treatment, either voluntarily (tA) or via external enforcement measures (?(C1+C2+A)). However, the population growth rate is balanced by relapse, such as direct relapse from treatment (?2T) and social relapses (peer and social influences) (?3AT), paired with the post-treatment exits (?1T). Consequently, the treatment population gradually increases and stabilizes around t = 24 months, converging to a positive equilibrium that reflects ongoing treatment interventions. Simultaneously, the abuse population initially grows due to chronic inflow but gradually stabilizes as individuals are drawn into treatment. In Figure 5(d), the two-variable linear system is simulated over time, where X1(t) represents the rate of population change in acute users (M) and X2(t) represents the rate of change in treatment population (T). Initially, X1(t) is found to increase due to the inflow of new acute users, while X2(t) rises as individuals enter treatment. Subsequently, both rates of change gradually stabilize, and the system approaches the endemic equilibrium, indicating a balance between the population of acute users and those present in treatment. The results reveal persistent relapse flows and ongoing treatment, which highlights the system’s capability to sustain both abuse liabilities and active interventions.

Figure 5: (a) Trajectories of medical users, (b) population when (?3, ?2) = (0, 0), (c) Abuse population vs. treatment with t = 36 months, (d) time-domain, X1(t) and X2(t).

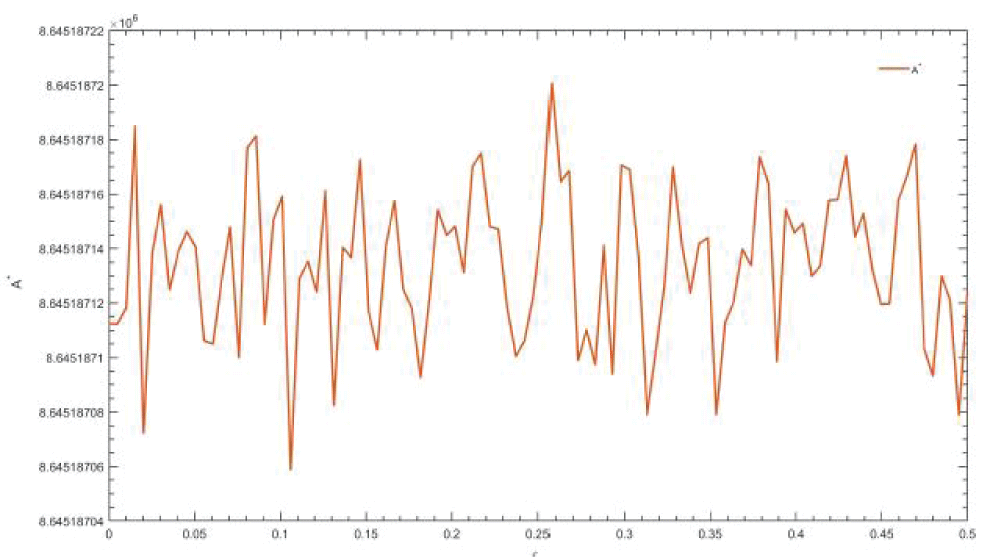

Figure 5: (a) Trajectories of medical users, (b) population when (?3, ?2) = (0, 0), (c) Abuse population vs. treatment with t = 36 months, (d) time-domain, X1(t) and X2(t).A single-parameter bifurcation analysis is performed to understand the influence of the treatment relapse rate (?2) against the long-term abuse compartment A at equilibrium for t = 200. The relapse rate (?2) is varied continuously over ?2 ∈ [0, 0.5] while all other parameters are fixed at base values:

The system is initialized with the population values:

In Figure 6, the analysis revealed a monotonic growth in A* (equilibrium abuse population) as ?2 increases. At lower relapse (?2 ˜ 0), the system stabilizes at smaller levels relative to the abuse, indicating that treatment programs with minimal relapse brought out longterm significant reductions in the abuse A* with no apparent bi-stability within the examined parameter range, concluding that relapse acts as a continuous enhancer of the problem, signifying a stronger destabilization highlighting the important role of treatment relapse ?2 in regulating long-term patterns.

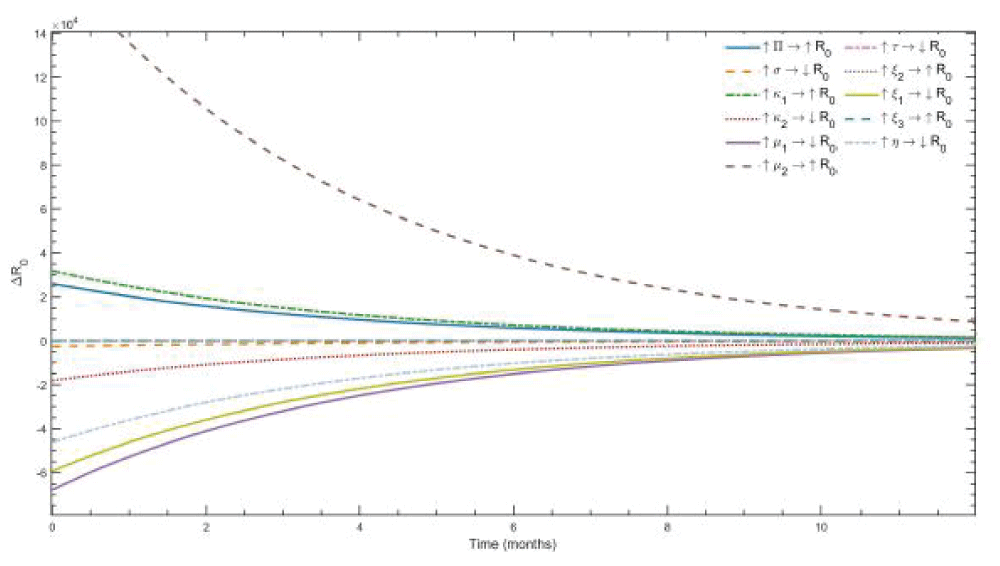

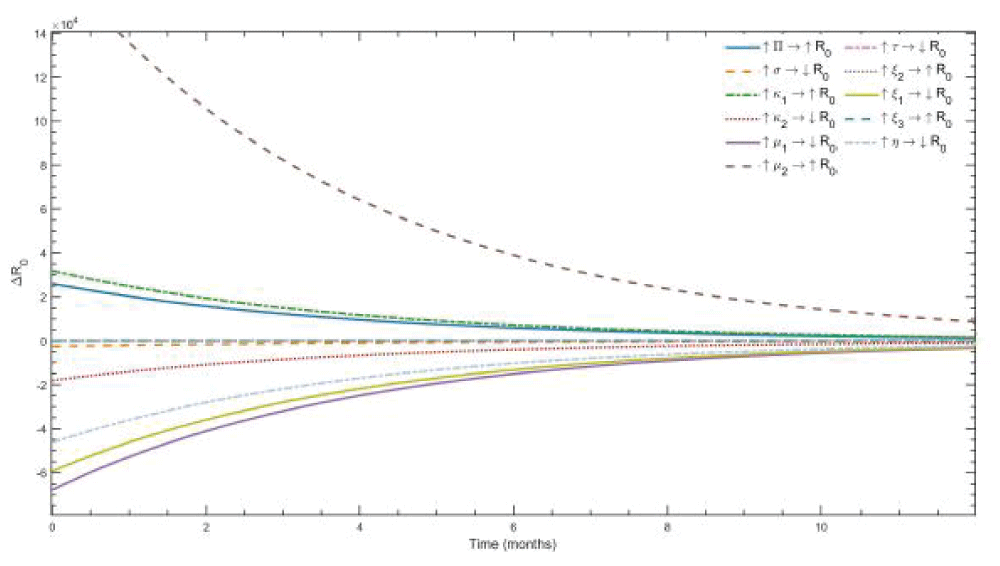

The sensitivity analysis of reproduction number R0 has been conducted by varying each of the parameters within defined bounds while maintaining all others at initial values and the deviations for 12 months are calculated.

From Figure 7, we observe that an increase in parameters such as the inflow of new prescriptions (?), progression rates - acute to chronic (?1), chronic to abuse (µ2), and the relapse rate from treatment (?2) consistently elevated the reproduction number R0 and are found to act as epidemic boosters sustaining the growth of the problem. The progression parameters (?1, µ2) contributed largely to the positive shifts in the deviations, while parameters associated with prevention and cessation exhibited a restricting influence on the reproduction number R0. Therefore, an increase in awareness (s), acute cessation (?2), chronic cessation (µ1), treatment-seeking (t), and successful treatment (?1) rates is found to reduce the reproduction potential of the system. Prevention awareness (s) and chronic cessation rate (µ1) exhibited the strongest deviation, considering them as key factors to control the problem. However, the role of law enforcement is observed to be less direct. Although strict enforcement contributed to a reduction in the R0, its effect is comparatively moderate against prevention and cessation rates, suggesting that enforcement measures are singularly not sufficient to achieve control in the absence of awareness and cessation complementary interventions.

Figure 7: Sensitivity of the basic reproduction number (R0) to progression parameter ?1 over 36 months.?1 is plotted as a function of time under varying awareness (s) and enforcement (?).

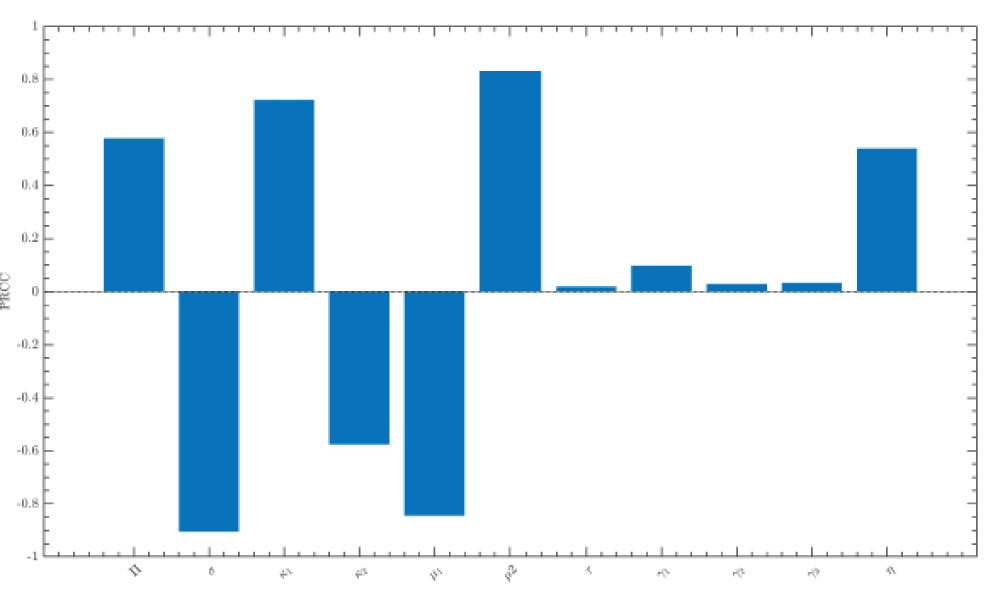

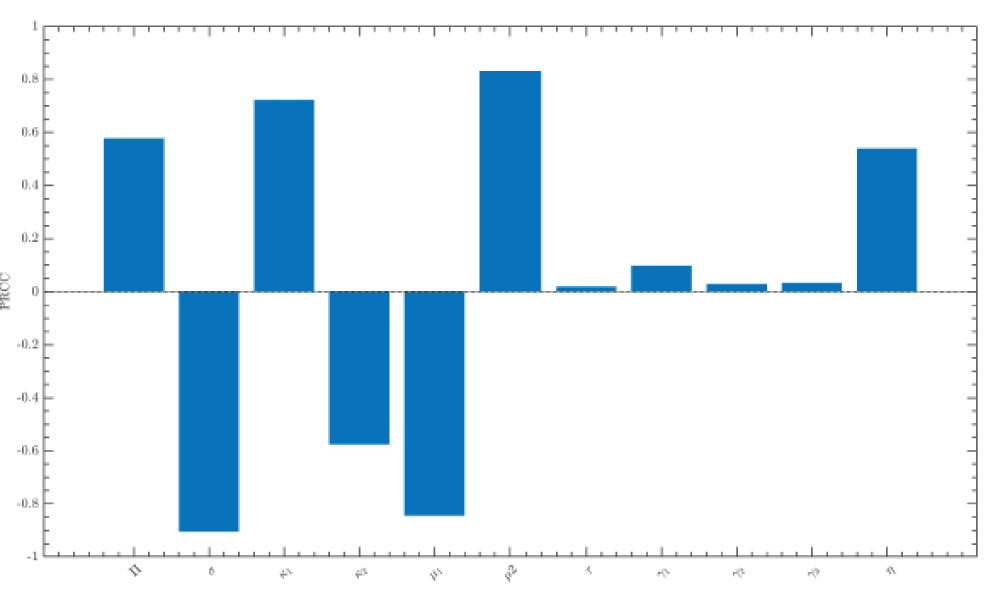

Figure 7: Sensitivity of the basic reproduction number (R0) to progression parameter ?1 over 36 months.?1 is plotted as a function of time under varying awareness (s) and enforcement (?).The partial rank correlation (PRCC) method is used to quantify and assess the influence of various model parameters on the abuse population size at equilibrium.

In Figure 8, we observe the strength and direction of the relationship between the input parameters and the equilibrium after t = 300 months. Parameters with positive PRCC values (?1, µ2, ?) are found to increase the abuse equilibrium when elevated, while parameters with negative PRCC values (s, ?2, µ1) contribute to suppressing A*. The law enforcement parameter (?) exhibited a weak or positive association in the Indian context due to limited enforcement effectiveness. The prevention awareness rate (s) is identified as the strongest negative correlation in relation to the abuser population, with a PRCC value of -0.89981, emphasizing the significant effect of awareness-related interventions in reducing the initiation of drug abuse and its progression. Similarly, the acute cessation rate (?2 = -0.57917) and chronic cessation rate (µ1 = -0.85813) exhibited negative values when associated with the abuser population, highlighting that improved cessation processes significantly decrease the long-term occurrences. In contrast, progression rates such as the acute-to-chronic (?1 = 0.76896) and chronic-to-abuse (µ2 = 0.83971) show strong positive correlations, verifying that acceleration through medical phases is the principal cause for the prevalence of abuse. The positive inflow of new prescriptions (? = 0.59467) contributes in maintaining the susceptible group with other parameters exerting relatively weaker effects such as the relapse rate from treatment (?2 = -0.016631), treatment success rate (?1 = 0.0088339), and social relapse rate (?3 = -0.054391) showing slight negative correlations with the treatment-seeking rate (t = 0.07896) being moderate in influence. The law enforcement rate (? = 0.57408) displays a reasonable positive correlation, indicating that enforcement-driven transfers to treatment may unintentionally preserve part of the relapse cycle, thereby boosting the abuse population under certain conditions. The PRCC analysis identified prevention awareness, acute cessation, and chronic cessation rates as the leading parameters for reducing the frequency of Tramadol abuse, while progression rates remain the strongest enhancers of the problem, emphasizing the importance of prevention-focused interventions and developing competent cessation pathways to control the prescriptions effectively.

Figure 8: Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) analysis of model parameters with respect to the basic reproduction number R0.

Figure 8: Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) analysis of model parameters with respect to the basic reproduction number R0.The proposed mathematical model of Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model (MRTAM) for the tramadol abusers assumes a uniform population and identical transition rate across compartment which overlooks the variations in susceptible and relapse individuals. Further, the absence of spatial structure and demographic classifications neglects transmission and networking processes, age, and region- specific behaviors.

The study investigates the dynamics of Tramadol abuse using Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model(MRTAM). The key effects of biological, behavioral, social and enforcement parameters were examined on the prevalence of abuse, treatment outcome and relapse cycles. Some concluding remarks are presented as follows:

The parameters values are hypothetical and based on certain report due to insufficient data. If proper clinical data and parameters are available, it would be possible to frame the model more realistically. The model assumes a uniform demographic population to clearly understand the effects of law enforcement (?) and relapse (?2) parameters in the control of tramadol abusers. The formulation of the model does not include a spatial structure, which provides a reliable basic reproduction number (R0) that thresholds with respect to the observed seizure data. The focus on assessing with detailed data from national agencies such as Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) records for in future work, the model may extend to include age-structured compartments and control techniques. This study can be strengthen with uncertainty and optimise intervention strategies to enhance the model's ability to capture age-specific differences and relapse patterns with respect to public health and enforcement planning.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

One of the authors, Nivedita Singh, acknowledges DST, New Delhi for providing financial assistance through INSPIRE-SHE scholarship (202000005307).

Caldwell WK, Freedman B, Settles L, Thomas MM, Camacho ET, Wirkus S. The Vicodin abuse problem: a mathematical approach. J Theor Biol. 2019 Dec 21;483:110003. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.110003. Epub 2019 Sep 9. PMID:31513802.

White E, Comiskey C. Heroin epidemics, treatment and ODE modelling. Math Biosci. 2007 Jul;208(1):312–324. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2006.10.008. Epub 2006 Nov 7. PMID:17174346.

Hogea CS, Murray BT, Sethian JA. Simulating complex tumor dynamics from avascular to vascular growth using a general level-set method. J Math Biol. 2006 Jul;53(1):86–134. doi:10.1007/s00285-006-0378-2. Epub 2006 Apr 28. PMID:16791651.

Mandal A, Tiwari PK, Pal S. Impact of awareness on environmental toxins affecting plankton dynamics: a mathematical implication. J Appl Math Comput. 2021;66:369–395. doi:10.1007/s12190-020-01441-5.

Nazmul SK, Pal S. Dynamics of an infected prey–generalist predator system with the effects of fear, refuge, and harvesting: deterministic and stochastic approach. Eur Phys J Plus. 2022;137:138. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-022-02348-9.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2024. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2024. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2024.html

World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence: forty-sixth report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. WHO Technical Report Series; No. 1057. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/ecdd

World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence: forty-seventh report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. WHO Technical Report Series; No. 1065. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/ecdd

Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK; National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance Use in India Investigators. Magnitude of substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019. Available from: https://www.lgbrimh.gov.in/resources/Addiction%20Medicine/elibrary/magnitude%20substance%20abuse%20india.pdf

Walwyn WM, Miotto KA, Evans CJ. Opioid pharmaceuticals and addiction: the issues, and research directions seeking solutions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 May 1;108(3):156–165. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.001. Epub 2010 Feb 25. PMID:20188495; PMCID:PMC3072810.

Befekadu GK, Zhu Q. Optimal control of diffusion processes pertaining to an opioid epidemic dynamical model with random perturbations. J Math Biol. 2019 Apr;78(5):1425–1438. doi:10.1007/s00285-018-1314-y. Epub 2018 Dec 4. PMID:30515526.

Nielsen S, MacDonald T, Johnson JL. Identifying and treating codeine dependence: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2018 Jun 4;208(10):451–461. doi:10.5694/mja17.00749. PMID:29848240.

Mukherjee D, Shukla L, Saha P, Mahadevan J, Kandasamy A, Chand P, Benegal V, Murthy P. Tapentadol abuse and dependence in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Mar;49:101978. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101978. Epub 2020 Feb 22. PMID:32120298.

Fulford GR, Barnes B. Mathematical modeling with case studies: a differential equation approach using Maple and MATLAB. London: Taylor & Francis; 2002.

Nyabadza F, Coetzee L. A systems dynamic model for drug abuse and drug-related crime in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Comput Math Methods Med. 2017;2017:4074197. doi:10.1155/2017/4074197. Epub 2017 May 7. PMID:28555161; PMCID:PMC5438861.

Brauer F, Chavez CC, Feng Z. Mathematical models in epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2019.

Martcheva M. An introduction to mathematical epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2015.

Srivastav AK, Ghosh M, Chandra P. Modeling dynamics of the spread of crime in a society. Stoch Anal Appl. 2019;37:991–1011. doi:10.1080/07362994.2019.1636658.

Mamo DK, Kinyanjui MN, Teklu SW, Hailu GK. Mathematical modeling and analysis of the co-dynamics of crime and drug abuse. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 2;14(1):26461. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75034-8. PMID:39488534; PMCID:PMC11531553.

Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Schnoll SH, Senay EC, Woody GE. A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and hydrocodone in patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 May;31(5):465–476. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.006. PMID:16716877.

Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, Bruneau J, Altice FL, Henderson G, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Larney S. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019 Oct 26;394(10208):1560–1579. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32229-9. Epub 2019 Oct 23. PMID:31657732; PMCID:PMC7068135.

McCabe JE. What works in policing?: the relationship between drug enforcement and serious crime. Police Q. 2008;11:389–409. doi:10.1177/1098611107306863.

Parmar A, Narasimha VL, Nath S. National drug laws, policies, and programs in India: a narrative review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024 Jan;46(1):5–13. doi:10.1177/02537176231170534. Epub 2023 Jun 11. PMID:38524944; PMCID:PMC10958082.

Dauhoo MZ, Korimboccus BSN, Issack SB. On the dynamics of illicit drug consumption in a given population. IMA J Appl Math. 2013;78:432–448. doi:10.1093/imamat/hxr058.

Vallath N, Tandon T, Pastrana T, Lohman D, Husain SA, Cleary J, Ramanath G, Rajagopal MR. Civil society-driven drug policy reform for health and human welfare—India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 Mar;53(3):518–532. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.362. Epub 2016 Dec 30. PMID:28042065.

Woody GE, Senay EC, Geller A, Adams EH, Inciardi JA, Schnoll S, Muñoz A, Cicero TJ. An independent assessment of MEDWatch reporting for abuse/dependence and withdrawal from Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Nov 24;72(2):163–168. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00198-4. PMID:14636971.

Muli FM. Mathematical analysis of drug and substance abuse model with treatment and policing. J Appl Math. 2025;2025:6666148. doi:10.1155/2025/6666148.

Mamo DK, Kinyanjui MN, Teklu SW, Hailu GK. Mathematical modeling and analysis of the co-dynamics of crime and drug abuse. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 2;14(1):26461. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75034-8. PMID:39488534; PMCID:PMC11531553.

Mikhaylov A, Bhatti IM, Dinçer H, Yüksel S. Integrated decision recommendation system using iteration-enhanced collaborative filtering, golden cut bipolar for analyzing the risk-based oil market spillovers. Comput Econ. 2022 Nov 10;60:1–34. doi:10.1007/s10614-022-10341-8. Epub ahead of print. PMID:36406765; PMCID:PMC9647255.

Irshad AS, Zakir MN, Rashad SS, Lotfy ME, Mikhaylov A, Elkholy MH, Pinter G, Senjyu T. Comparative analyses and optimizations of hybrid biomass and solar energy systems based upon a variety of biomass technologies. Energy Convers Manag X. 2024;23:100640. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100640.

Inciardi JA, Cicero TJ, Muñoz A, Adams EH, Geller A, Senay EC, Woody GE. The diversion of Ultram, Ultracet, and generic tramadol HCl. J Addict Dis. 2006;25:53–58. doi:10.1300/J069v25n02_08.

Ehrenreich H, Poser W. Dependence on tramadol. Clin Investig. 1993;72:76. doi:10.1007/BF00231123.

Freye E, Levy J. Acute abstinence syndrome following abrupt cessation of long-term use of tramadol (Ultram): a case study. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:307–311. doi:10.1053/eujp.2000.0187.

Sarkar S, Nebhinani N, Singh SM, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Tramadol dependence: a case series from India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012 Jul;34(3):283–285. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.106038. PMID:23440178; PMCID:PMC3573583.

Senay EC, Adams EH, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A, Schnoll SH, Woody GE, Cicero TJ. Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:233–241. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00321-6.

Leo RJ, Narendran R, DeGuiseppe B. Methadone detoxification of tramadol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Oct;19(3):297–299. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00098-2. PMID:11027901.

Tjäderborn M, Jönsson AK, Ahlner J, Hägg S. Tramadol dependence: a survey of spontaneously reported cases in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 Dec;18(12):1192–1198. doi:10.1002/pds.1838. PMID:19827010.

Duke AN, Bigelow GE, Lanier RK, Strain EC. Discriminative stimulus effects of tramadol in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:255–262. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.181131.

Preston KL, Jasinski DR, Testa M. Abuse potential and pharmacological comparison of tramadol and morphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;27:7–17. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(91)90081-9.

Pandey D. Opioids in India: managing pain and addiction. New Delhi: Social and Political Research Foundation; 2020. Available from: https://sprf.in/opioids-in-india-managing-pain-and-addictions/

Narcotics Control Bureau. Annual report 2023–24. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 2024. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport27122024.pdf

Singh SS, Singh N, Handique S. A Model of the Enforcement of Laws in Tramadol Drug Abusers. IgMin Res. January 08, 2026; 4(1): 006-014. IgMin ID: igmin327; DOI:10.61927/igmin327; Available at: igmin.link/p327

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Mizoram University, Tanhril, Aizawl, 796004, Mizoram, India

#These authors contributed equally to this work

Address Correspondence:

SS Singh, Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, Mizoram University, Tanhril, Aizawl, 796004, Mizoram, India, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Singh SS, Singh N, Handique S. A Model of the Enforcement of Laws in Tramadol Drug Abusers. IgMin Res. January 08, 2026; 4(1): 006-014. IgMin ID: igmin327; DOI:10.61927/igmin327; Available at: igmin.link/p327

Copyright: 2026 Singh SS, et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Figure 1: Structure of tramadol, C16H25NO2....

Figure 1: Structure of tramadol, C16H25NO2....

Figure 2: Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model, MRTAM....

Figure 2: Multiple Relapse Tramadol Abuse Model, MRTAM....

Figure 3: (a) Effect of awareness rate (σ) on the abuse pop...

Figure 3: (a) Effect of awareness rate (σ) on the abuse pop...

Figure 4: Eigenvalues of the system of differential equation...

Figure 4: Eigenvalues of the system of differential equation...

Figure 5: (a) Trajectories of medical users, (b) population ...

Figure 5: (a) Trajectories of medical users, (b) population ...

Figure 6: Bifurcation analysis of equilibrium abuser populat...

Figure 6: Bifurcation analysis of equilibrium abuser populat...

Figure 7: Sensitivity of the basic reproduction number (R0) ...

Figure 7: Sensitivity of the basic reproduction number (R0) ...

Figure 8: Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) analys...

Figure 8: Partial Rank Correlation Coefficient (PRCC) analys...

Caldwell WK, Freedman B, Settles L, Thomas MM, Camacho ET, Wirkus S. The Vicodin abuse problem: a mathematical approach. J Theor Biol. 2019 Dec 21;483:110003. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2019.110003. Epub 2019 Sep 9. PMID:31513802.

White E, Comiskey C. Heroin epidemics, treatment and ODE modelling. Math Biosci. 2007 Jul;208(1):312–324. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2006.10.008. Epub 2006 Nov 7. PMID:17174346.

Hogea CS, Murray BT, Sethian JA. Simulating complex tumor dynamics from avascular to vascular growth using a general level-set method. J Math Biol. 2006 Jul;53(1):86–134. doi:10.1007/s00285-006-0378-2. Epub 2006 Apr 28. PMID:16791651.

Mandal A, Tiwari PK, Pal S. Impact of awareness on environmental toxins affecting plankton dynamics: a mathematical implication. J Appl Math Comput. 2021;66:369–395. doi:10.1007/s12190-020-01441-5.

Nazmul SK, Pal S. Dynamics of an infected prey–generalist predator system with the effects of fear, refuge, and harvesting: deterministic and stochastic approach. Eur Phys J Plus. 2022;137:138. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-022-02348-9.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). World Drug Report 2024. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2024. Available from: https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/world-drug-report-2024.html

World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence: forty-sixth report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024. WHO Technical Report Series; No. 1057. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/ecdd

World Health Organization. WHO Expert Committee on Drug Dependence: forty-seventh report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2025. WHO Technical Report Series; No. 1065. Available from: https://www.who.int/groups/ecdd

Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK; National Survey on Extent and Pattern of Substance Use in India Investigators. Magnitude of substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India; 2019. Available from: https://www.lgbrimh.gov.in/resources/Addiction%20Medicine/elibrary/magnitude%20substance%20abuse%20india.pdf

Walwyn WM, Miotto KA, Evans CJ. Opioid pharmaceuticals and addiction: the issues, and research directions seeking solutions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010 May 1;108(3):156–165. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.01.001. Epub 2010 Feb 25. PMID:20188495; PMCID:PMC3072810.

Befekadu GK, Zhu Q. Optimal control of diffusion processes pertaining to an opioid epidemic dynamical model with random perturbations. J Math Biol. 2019 Apr;78(5):1425–1438. doi:10.1007/s00285-018-1314-y. Epub 2018 Dec 4. PMID:30515526.

Nielsen S, MacDonald T, Johnson JL. Identifying and treating codeine dependence: a systematic review. Med J Aust. 2018 Jun 4;208(10):451–461. doi:10.5694/mja17.00749. PMID:29848240.

Mukherjee D, Shukla L, Saha P, Mahadevan J, Kandasamy A, Chand P, Benegal V, Murthy P. Tapentadol abuse and dependence in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Mar;49:101978. doi:10.1016/j.ajp.2020.101978. Epub 2020 Feb 22. PMID:32120298.

Fulford GR, Barnes B. Mathematical modeling with case studies: a differential equation approach using Maple and MATLAB. London: Taylor & Francis; 2002.

Nyabadza F, Coetzee L. A systems dynamic model for drug abuse and drug-related crime in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Comput Math Methods Med. 2017;2017:4074197. doi:10.1155/2017/4074197. Epub 2017 May 7. PMID:28555161; PMCID:PMC5438861.

Brauer F, Chavez CC, Feng Z. Mathematical models in epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2019.

Martcheva M. An introduction to mathematical epidemiology. New York: Springer; 2015.

Srivastav AK, Ghosh M, Chandra P. Modeling dynamics of the spread of crime in a society. Stoch Anal Appl. 2019;37:991–1011. doi:10.1080/07362994.2019.1636658.

Mamo DK, Kinyanjui MN, Teklu SW, Hailu GK. Mathematical modeling and analysis of the co-dynamics of crime and drug abuse. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 2;14(1):26461. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75034-8. PMID:39488534; PMCID:PMC11531553.

Adams EH, Breiner S, Cicero TJ, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Schnoll SH, Senay EC, Woody GE. A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and hydrocodone in patients with chronic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006 May;31(5):465–476. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.006. PMID:16716877.

Degenhardt L, Grebely J, Stone J, Hickman M, Vickerman P, Marshall BDL, Bruneau J, Altice FL, Henderson G, Rahimi-Movaghar A, Larney S. Global patterns of opioid use and dependence: harms to populations, interventions, and future action. Lancet. 2019 Oct 26;394(10208):1560–1579. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32229-9. Epub 2019 Oct 23. PMID:31657732; PMCID:PMC7068135.

McCabe JE. What works in policing?: the relationship between drug enforcement and serious crime. Police Q. 2008;11:389–409. doi:10.1177/1098611107306863.

Parmar A, Narasimha VL, Nath S. National drug laws, policies, and programs in India: a narrative review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2024 Jan;46(1):5–13. doi:10.1177/02537176231170534. Epub 2023 Jun 11. PMID:38524944; PMCID:PMC10958082.

Dauhoo MZ, Korimboccus BSN, Issack SB. On the dynamics of illicit drug consumption in a given population. IMA J Appl Math. 2013;78:432–448. doi:10.1093/imamat/hxr058.

Vallath N, Tandon T, Pastrana T, Lohman D, Husain SA, Cleary J, Ramanath G, Rajagopal MR. Civil society-driven drug policy reform for health and human welfare—India. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017 Mar;53(3):518–532. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.362. Epub 2016 Dec 30. PMID:28042065.

Woody GE, Senay EC, Geller A, Adams EH, Inciardi JA, Schnoll S, Muñoz A, Cicero TJ. An independent assessment of MEDWatch reporting for abuse/dependence and withdrawal from Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride). Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003 Nov 24;72(2):163–168. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(03)00198-4. PMID:14636971.

Muli FM. Mathematical analysis of drug and substance abuse model with treatment and policing. J Appl Math. 2025;2025:6666148. doi:10.1155/2025/6666148.

Mamo DK, Kinyanjui MN, Teklu SW, Hailu GK. Mathematical modeling and analysis of the co-dynamics of crime and drug abuse. Sci Rep. 2024 Nov 2;14(1):26461. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-75034-8. PMID:39488534; PMCID:PMC11531553.

Mikhaylov A, Bhatti IM, Dinçer H, Yüksel S. Integrated decision recommendation system using iteration-enhanced collaborative filtering, golden cut bipolar for analyzing the risk-based oil market spillovers. Comput Econ. 2022 Nov 10;60:1–34. doi:10.1007/s10614-022-10341-8. Epub ahead of print. PMID:36406765; PMCID:PMC9647255.

Irshad AS, Zakir MN, Rashad SS, Lotfy ME, Mikhaylov A, Elkholy MH, Pinter G, Senjyu T. Comparative analyses and optimizations of hybrid biomass and solar energy systems based upon a variety of biomass technologies. Energy Convers Manag X. 2024;23:100640. doi:10.1016/j.ecmx.2024.100640.

Inciardi JA, Cicero TJ, Muñoz A, Adams EH, Geller A, Senay EC, Woody GE. The diversion of Ultram, Ultracet, and generic tramadol HCl. J Addict Dis. 2006;25:53–58. doi:10.1300/J069v25n02_08.

Ehrenreich H, Poser W. Dependence on tramadol. Clin Investig. 1993;72:76. doi:10.1007/BF00231123.

Freye E, Levy J. Acute abstinence syndrome following abrupt cessation of long-term use of tramadol (Ultram): a case study. Eur J Pain. 2000;4:307–311. doi:10.1053/eujp.2000.0187.

Sarkar S, Nebhinani N, Singh SM, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Tramadol dependence: a case series from India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012 Jul;34(3):283–285. doi:10.4103/0253-7176.106038. PMID:23440178; PMCID:PMC3573583.

Senay EC, Adams EH, Geller A, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A, Schnoll SH, Woody GE, Cicero TJ. Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2003;69:233–241. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00321-6.

Leo RJ, Narendran R, DeGuiseppe B. Methadone detoxification of tramadol dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2000 Oct;19(3):297–299. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00098-2. PMID:11027901.

Tjäderborn M, Jönsson AK, Ahlner J, Hägg S. Tramadol dependence: a survey of spontaneously reported cases in Sweden. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009 Dec;18(12):1192–1198. doi:10.1002/pds.1838. PMID:19827010.

Duke AN, Bigelow GE, Lanier RK, Strain EC. Discriminative stimulus effects of tramadol in humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:255–262. doi:10.1124/jpet.111.181131.

Preston KL, Jasinski DR, Testa M. Abuse potential and pharmacological comparison of tramadol and morphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1991;27:7–17. doi:10.1016/0376-8716(91)90081-9.

Pandey D. Opioids in India: managing pain and addiction. New Delhi: Social and Political Research Foundation; 2020. Available from: https://sprf.in/opioids-in-india-managing-pain-and-addictions/

Narcotics Control Bureau. Annual report 2023–24. New Delhi: Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India; 2024. Available from: https://www.mha.gov.in/sites/default/files/AnnualReport27122024.pdf