Macrorhabdus ornithogaster-associated Avian Macrorhabdosis: A Narrative Review

Veterinary ScienceReceived 01 Apr 2025 Accepted 05 May 2025 Published online 06 May 2025

ISSN: 2995-8067 | Quick Google Scholar

Received 01 Apr 2025 Accepted 05 May 2025 Published online 06 May 2025

Avian macrorhabdosis is a disease of wild and captive birds (psittacines, passerines and other species) distributed worldwide, and is caused by the opportunistic yeast Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. The disease is usually chronic, and is manifested by nonspecific clinical signs (emaciation, anorexia, depression, cachexia and ultimately death), or gastrointestinal signs (regurgitation or attempted vomiting, watery diarrhea, and weight loss despite preserved appetite). It can also occur in a subclinical form, while the clinical disease can last for weeks, months (or even years). Diagnosis and therapy are still challenging for bird specialists for many reasons. During life, the diagnosis is made directly from stool smears after Gram staining by finding characteristic large, Gram-positive, 20 μm - 80 μm long and 3 μm - 4 μm wide rods, as well as a smear of the isthmus (proventricular-ventricular junction) after dissection. Early detection is possible using newly developed PCR tests. The only available drug against avian macrorhabdosis is amphotericin B, which is not effective in many cases regardless of the dose and duration of therapy. Although many birds have the causative agent in their digestive system, the disease is most likely to occur as a result of weakened immunity due to stress, poor hygiene, improper housing conditions and improper feeding, so regular periodic testing for macrorhabdosis is necessary.

Avian macrorhabdosis is a well-known disease of various bird species worldwide. The disease is known in older literature as megabacteriosis because for many years it was thought to be caused by bacteria [-]. More recent studies indicate a fungal etiology, caused by Macrorhabdus ornithogaster, an anamorphic, ascomycetous fungus. There are numerous arguments, such as Y-shaped budding, a eukaryotic nucleus, and a cell wall containing cellulose and chitin in a three-layer structure, which is much thicker than the bacterial cell wall []. The FISH (fluorescence-in-situ-hybridisation) method using a probe for eukaryotic rRNA and PCR tests using primers for 18S rDNA and 26S rDNA characteristic of fungi were decisive [-]. This yeast from the genus Macrorhabdus is classified in the clade saccharomyceta (class Saccharomycetes and order Saccharomycetales (incertae sedis)). It is a flat, narrow rod 3 μm - 4 µm wide and 20 μm - 80 µm long that slowly grows in microaerophilic conditions and stains Gram-positive. Size and length can vary considerably, as yeasts found in feces are generally larger and longer than those found in the digestive tract of live birds [,,]. Vegetative forms are elongated (2 μm - 20 μm), divide by fission, and are found singly or in short chains of two to four []. In laboratory conditions, they grow, albeit slowly, in cell culture medium supplemented with dextrose, fetal calf serum and antibiotics []. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster is a yeast found only at the narrow junction (isthmus) between the proventriculus and ventriculus in numerous bird species. This pathogen is considered a commensal in many wild bird species because they do not show signs of disease (although it is found in the digestive system and most individuals never become ill), while in captive birds it is a very common cause of illness and death, especially in some smaller parrot species and certain passerine species [].

Avian macrorhabdosis is a disease distributed worldwide, and the causative agent has been identified in wild and captive birds, including a wide range of psittacines, passerines, poultry, and other species [,]. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster was first identified and described in finches, canaries [,], and small parrots (budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) [-], lovebirds (Agapornis sp.) and rarely in cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus) [,]. In addition, it has been recorded in some large parrots, ostriches [], rheas [], zebra finches, free-range chickens [], turkeys, guinea fowl, pigeons [], toucans, chukar partridges [], ibises, wild passerines, ducks, and wading birds []. Gerlach [] listed about 50 species of birds, but highlighted budgerigars, lovebirds and canaries as the birds with the highest incidence of avian macrorhabdosis. Some authors, also add to the list of susceptible species for macrorhabdosis South American parrotlets, group of the smallest parrot species from the genera: Forpus sp., Nannopsittaca sp., and Touit sp. Using fecal smears from live birds or random finding of proventriculus cytological samples taken at necropsy of birds (that died of other causes), [] Piasecki, et al. found M. ornithogaster in a total of 45 species of exotic and wild birds in Poland as follows: budgerigars, canaries, cockatiels macaws (Ara ararauna); cockatoos (Cacatua alba, C. goffini, C. tenuirostris, C. moluccensis, and C. sulphurea), African grey parrots (Psittacus erithacus), ringneck parrots (Psittacula krameri), Eclectus roratus, Nandayus nenday, Neophema sp., kakariki parrots (Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae), patagonian conures (Cyanoliseus patagonus), Polytelis anthopeplus, monk parrots (Myiopsitta monachus), red-rumped parrots (Psephotus haematonotus), rosselas (Platycercus eximius, Platycercus adsitus), cut-throat finches (Amadina fasciata), long-tailed finches (Poephila acuticauda), Gouldian finches (Chloebia gouldiae), zebra finches (Poephila guttata), Java sparrow (Lonchura oryzivora), greenfinches (Chloris chloris), common hill myna (Gracula religiosa), chaffinches (Fringilla coelebs), rooks (Corvus frugilegus), carrion crows (Corvus corone), jackdaws (Corvus monedula), common magpie (Pica pica), Eurasian blackcaps (Sylvia atricapilla), Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis), common blackbirds (Turdus melura), song thrush (Turdus philomelos), geese, quails, pigeons and doves. In Brazil, Martins, et al. [] found the presence of Macrorhabdus in healthy urban pigeons (Columba livia) and ruddy ground doves (Columbina talpacoti). This pathogen is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in certain groups of birds, (as pets, kept by owners, in zoos, etc.) [,].

Avian macrorhabdosis is a chronic progressive gastrointestinal disease of various bird species characterized by nonspecific clinical signs such as emaciation, anorexia, cachexia and ultimately death. The most common course of infection with M. ornithogaster is subclinical and chronic, but it can also lead to gastrointestinal signs []. The first symptoms observed are usually weight loss, despite a preserved appetite, and depression []. Most birds have watery diarrhea that can vary in color from black to khaki. The black color of the feces (melena) is the result of ulceration of the glandular stomach, and some birds may die suddenly. However, the disease usually has a chronic course, which can last for weeks, months or even years [,,,].

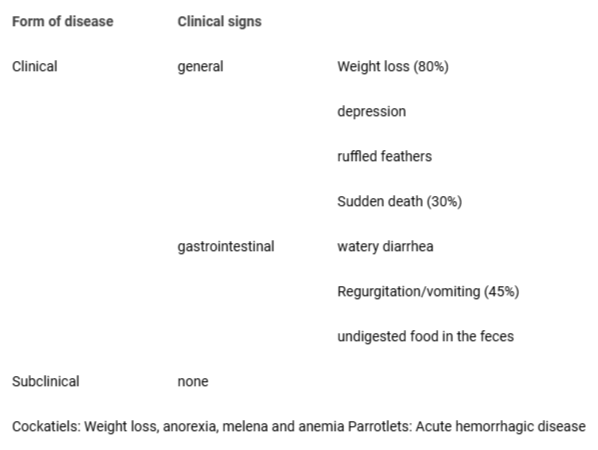

Considering the non-specific clinical signs caused by M. ornithogaster, the specificity and ineffectiveness of therapy and the ways or procedures of interpreting diagnostic procedures, the disease represents a serious challenge for bird specialists. Along with regurgitation or attempted vomiting, diarrhea and chronic weight loss are the most common signs described in a various bird species. Young and adult birds can get sick, while the budgerigars get sick most often in middle age. The budgerigars may stop eating or even more often overeat, but suddenly lose weight. As their feathers are often ruffled, the owner does not notice this sudden weight loss in time. Due to diarrhea, undigested food may be observed (e.g. millet grains, etc.) in the feces and/or wet food on the head around the beak that stuck to the feathers during regurgitation. In parrotlets, the most common form is acute hemorrhagic disease, while in cockatiels, weight loss, anorexia, melena and anemia are occasionally observed (Table 1).

Despite advances in veterinary medicine, diagnosis and therapy are still challenging [-]. Diagnosis is easily made by postmortem examination of the outline of the isthmus and histopathological examination of the proventriculus and ventriculus [], although the finding of the organism at these sites may be incidental even in some healthy birds. These tests are not sufficient because a negative result does not exclude infection. It is recommended to take samples for three consecutive days because it is commonly believed that the pathogen is not constantly excreted in feces []. Direct observation of the Macrorhabdus in fecal smears is confirmed by the finding of characteristic large, Gram-positive, 20-80 μm long and 3-4 μm wide rods, after Gram staining []. The same finding as in fecal smears can be found in the isthmus, proventriculus and ventriculus after Gram staining. Similarly, detection of infection in live birds is either by direct observation of the organism in the feces or by detection using PCR [] early detection and treatment using the properties of the PCR test can help prevent disease progression [-]. Lang, et al. 2025 [] developed a new analytical qPCR test for the detection of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster that is likely to improve early pathogen detection and treatment of macrorhabdosis.

Cultivation of this pathogen on classic media for growing fungi and molds, Sabouraud or similar nutrient media, is not routinely used in diagnostics, but is possible []. Culturing this pathogen is possible, though further research is needed, as well as susceptibility testing and development of effective antifungal drugs. Culturing on Basal Medium Eagle or medium with chicken serum, 20% fetal bovine serum, 5% sucrose, 100 U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin and 25 µg/mL chloramphenicol at pH 3 to 4 and 42 °C under microaerophilic conditions was used by the above-mentioned author. Culture of this pathogen is possible, but further research is needed, as well as susceptibility testing and development of effective antifungal drugs.

Differential diagnosis: Macrorhabdosis should be distinguished from candidiasis, trichomoniasis, giardiasis, bacterial and other fungal infections of the crop and stomach, helminth infections of the digestive tract, Bornavirus infection, crop foreign bodies, gastric opstuction and heavy metal poisoning [].

In affected birds, the proventriculus is enlarged due to thickening of the walls. Microscopic findings show moderate to severe lymphoplasmacytic and heterophilic inflammation of the proventriculus and ventriculus, and numerous microorganisms are present in the mucus of the proventricular crypts and, less frequently, in the epithelium. At necropsy, gross lesions show atrophy of the pectoral muscle, accompanied by proventricular dilatation [,]. The walls of the proventricle and ventricle are thickened with thick white mucus, with loosening of the koilin layer and significant hemorrhages and ulcerations in the proventricular-ventricular junction []. Histologically, Gram- or silver-stained sections of the proventriculus show pale eosinophilic microorganisms at the tips of the isthmus glands arranged in parallel. In advanced cases, atrophy of the isthmus glands and ulceration of the isthmus and gizzard koilin develop. Before ulceration, inflammation or lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lamina propria of the isthmus glands may occur [].

Numerous antifungal drugs are not effective in treating this disease (iodine preparations, lufenuron, fluconazole, ketoconazole, itraconazole, and terbinafine). There were only a few antifungal drugs effective for treating M. ornithogaster, but due to the development of resistance to the nystatin, only amphotericin B remains the treatment of choice [-]. Amphotericin B is widely used to treat Macrorhabdus ornithogaster infections, although its efficacy is only partially successful. In some studies on budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) and lovebirds (Agapornis roseicollis), amphotericin B was administered at a dose of 100 mg/kg twice daily for 30 days, and In another study, experimentally infected chickens received amphotericin B at doses of 25 mg/kg and 100 mg/kg, administered twice daily for 10 days. In chickens, the treatment failure rate was very high, 80.4%. It is assumed that amphotericin B significantly reduces the number of pathogens in the digestive tract, giving negative results. Despite that, after a certain period of time the pathogen can be found again in the feces.

Poleschinski, et al. [] investigated the efficacy of amphotericin B treatment. Animals were treated for 28 days at a dose of 0.1 mg/mL in drinking water and another group was given the same dose in drinking water for 28 days and an additional 100 mg/kg PO every 12 hours for 10 days. After 2 weeks of treatment, fecal samples were retested by PCR and more than half (56.4%) of the treated birds were negative for M. ornithogaster. Without catching the bird twice daily, and administering the drug orally into beak, a less stressful alternative is the administration of amphotericin B via drinking water only, which has been shown to be effective in more than 50% of cases.

According to Carpenter [], amphotericin B can be applied to budgerigars in drinking water for 28 days at a dose of 1000 mg/L of water or by gavage at 100-109 mg/kg PO every 12 h for 10-30 days, while for other bird species, doses and methods of administration are not specified. The resistance was reported in budgerigars in Australia [].

There are also some alternative treatments such as acidification of food or drinking water (with apple vinegar, citric acid, etc.), which actually has no scientific basis because the causative agent grows in an acidic medium at pH 3 to 4. Some authors report that adding acetic acid, citric acid, or grapefruit juice to drinking water can reduce infection [,]. Probiotics such as Lactobacillus acidophilus can be used as supportive therapy.

This narrative review synthesizes data from published studies and case reports on the prevalence, diagnosis, and outcomes of avian macrorhabdosis across bird species and geographic regions. A total of 42 studies were included, published between 1990 and 2025, covering over 75 avian species. The most commonly reported hosts were:

Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus) 60% of studies,

Canaries (Serinus canaria) and lovebirds (Agapornis spp.) 25%,

Other psittacine and passerine species 15%.

The average sample size across studies was 67 birds (range: 6-310). Reported prevalence rates varied significantly depending on bird species, geographic location, and diagnostic method (e.g. the Prevalence rates ranged from 10% to 65% in budgerigars). Geographic differences of prevalence were noted (Europe ~28%, Asia 50% in backyard flocks, and lower prevalence in South America < 15%). These prevalence rates were based on cytological and PCR-based diagnostic techniques, which differ in sensitivity. Several studies compared diagnostic methods. Sensitivity was: cytology (wet mount from feces) 55% - 70%, PCR > 90% (but not widely available in routine practice), and histopathology considered definitive in post-mortem diagnoses. A limited number of studies reported false negatives with cytology, especially in asymptomatic carriers.

In various species of parrots, the causative agent of macrorhabdosis can be found in the digestive system or as an incidental finding in swabs of the intermediate part of the proventriculus and gizzard during dissection of healthy birds. The occurrence of M. ornithogaster in swab preparations from the proventricular-ventricular junction than in fecal smears [,]. It is not known why some species of psittacines get sick more often than others. The most common parrots that suffer from avian macrorhabdosis are budgerigars, cockatiels, lovebirds, and among passerines, canaries. The high percentage of positive parrots from some groups of large parrots such as macaws and African grey parrots is surprising because cases of clinical form of this disease in these species are rarely reported. Piasecki, et al. [] were found M. ornithogaster in 26.1% of wild birds and 28.7% of exotic birds and parrots (65.0% budgerigars, 41.6% macaws, 33.3% African grey parrots, 26.9% cockatiels and 16.7% lovebirds, 9.3% canaries, 1.2% finches). In Belgium, the percentage of canaries with M. ornithogaster was 28% [], and in the Netherlands 33.3% [], i.e. 2-3 times higher than in Poland. Determining the causative agent in fecal smears is not completely accurate, because due to the periodic excretion from the macroorganism and the intensity of the causative agent's invasion, the findings may be falsely negative. In addition, presence of the causative agent in feces does not necessarily indicate clinical illness, because the causative agent is often found in the feces of healthy birds. Under the influence of stress and other accompanying diseases, the appearance of clinical signs of the disease may occur. Macrorhabdosis (megabacteriosis) was diagnosed respectively in 22.5% of budgerigars in Belgium []. In reared passerine birds (finches), Gouldian finches (Chloebia gouldiae) showed a very low sensitivity to the invasion of M. ornithogaster, as the causative agent was found in only one zebra finch (Poephila guttata), while none were found in cut-throat finches (Amadina fasciata) and long-tailed finches (Poephila acuticauda) [].

The diagnostic procedure in specialized avian clinics is similar, and is based mainly on clinical signs and further examinations of feces, on the basis of which the disease is suspected []. After that, a native or a Gram-stained preparation can be made from fecal samples (usually collected over 3 consecutive days). Some make a final diagnosis based on a PCR test [-]. Culturing M. ornithogaster on nutrient media is not a common diagnostic procedure, but is used in some research due to the complexity and special conditions required by this pathogen. Delayed or missed diagnoses can result in prolonged morbidity. They also increase transmission risk and lead to poor treatment outcomes []. The development of more sensitive and specific diagnostic approaches, such as molecular assays or antigen-based tests would enable earlier detection, improved epidemiological understanding, and timely intervention. Highlighting these gaps in treatment and diagnosis underscores the critical importance of further research into the pathophysiology of M. ornithogaster, drug susceptibility profiling, and novel diagnostic modalities.

After diagnosis, if birds are asymptomatic, some clinics defer immediate treatment, they treat the birds after the first signs of illness [,]. Current therapeutic options are limited and inconsistently effective, primarily relying on amphotericin B or off-label antifungals with variable outcomes. Moreover, the organism’s unique fungal characteristics and its localization in the isthmus of the avian gastrointestinal tract complicate drug delivery and efficacy. Treatment with amphotericin B is currently the only reliable treatment, although the outcome of treatment is not often satisfactory. Very often, treatment is unsuccessful or the success is temporary because the bird is not completely cured. After the prescribed treatment, the birds may test negative temporarily; however, the disease can recur intermittently several times despite treatment [,,]. There is a pressing need for the development of novel antifungal agents with improved targeting, bioavailability, and reduced toxicity. Such therapeutics could not only improve outcomes but also help mitigate the risk of resistance stemming from sub therapeutic or empirical treatment.

Parallel to therapeutic limitations is the inadequacy of existing diagnostic tools. Diagnosis typically relies on microscopic examination of fecal samples, which is often insensitive and operator-dependent. Future studies should prioritize not only therapeutic innovation but also the establishment of standardized, validated diagnostic protocols, ultimately guiding better clinical management and reducing disease burden in affected avian populations. Additionally, studies investigating antifungal resistance patterns and pharmacodynamics in avian species are critically lacking.

Addressing these diagnostic and therapeutic gaps is essential for improving animal welfare, preventing disease spread, and enhancing our understanding of host-pathogen dynamics. Future studies should focus on the development and validation of rapid, non-invasive diagnostic assays; screening and characterization of new antifungal compounds or treatment regimens, and investigating the microbiome’s role in susceptibility and chronic colonization or exploring potential vaccines or immunomodulatory therapies.

Avian macrorhabdosis is most common in psittacines and passerine birds, but in most cases this opportunistic yeast does not cause clinical disease. Although many birds harbor the causative agent in their digestive tract, the disease is most likely to occur as a result of weakened immunity due to stress, poor hygiene, poor housing and feeding conditions, so regular periodic testing for macrorhabdosis is necessary. Future studies should focus on the development and validation of rapid diagnostic assays, and development of new antifungal compounds.

Scanlan CM, Graham DL. Characterization of a gram-positive bacterium from the proventriculus of budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Avian Dis. 1990 Jul-Sep;34(3):779-86. PMID: 2241708.

Horvatek Tomić D, Lukač M, Lozica L, Budicin E, Gottstein Ž. Avian macrorhabdosis – a well-known disease with a new name. Hrvatski veterinarski vjesnik. 2024;32(1):29-33.

Werther, K., Schocken-Iturrino, R.P., Verona, C.E.S., Barros, L.S.S., 2000. Megabacteriosis occurrence in budgerigars, canaries and lovebirds in Ribeirão Preto region-Sao Paulo state-Brazil. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2(2), 183-187.

Gerlach H. Megabacteriosis. Semin. Avian Exotic Pet Med. 2001; 10:12-19.

Ravelhofer-Rotheneder K, Engelhardt H, Wolf O, Amann R, Breuer W, Kösters J. Taxonomic classification of megabacterial isolates from budgerigars (Mellopsittacus undulatus Shaw, 1805). Tierärztl. Prax. 2000; 28:415-420.

Tomaszewski EK, Logan KS, Snowden KF, Kurtzman CP, Phalen DN. Phylogenetic analysis identifies the 'megabacterium' of birds as a novel anamorphic ascomycetous yeast, Macrorhabdus ornithogaster gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003 Jul;53(Pt 4):1201-1205. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02514-0. PMID: 12892150.

Abd El-Ghany W. Avian macrorhabdosis (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) causing proventriculitis: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and control: Vet. Integr Sci. 2024;22(3):921-31.

Phalen DN. Update on the diagnosis and management of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (formerly megabacteria) in avian patients. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2014 May;17(2):203-10. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2014.01.005. PMID: 24767742.

Powers LV, Mitchell MA, Garner MM. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection and Spontaneous Proventricular Adenocarcinoma in Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Vet Pathol. 2019 May;56(3):486-493. doi: 10.1177/0300985818823773. Epub 2019 Jan 16. PMID: 30651051.

Borrelli L, Dipineto L, Rinaldi L, Romano V, Noviello E, Menna LF, Cringoli G, Fioretti A. New Diagnostic Insights for Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 Nov;53(11):3448-50. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01564-15. Epub 2015 Aug 19. PMID: 26292316; PMCID: PMC4609710.

Luján Vega C, Gonzales-Gustavson E, Alfonso C. Detection of avian gastric yeast (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) in exotic small psittacines and passerines of aviaries in Lima, Peru. Presented at: Latin American Veterinary Conference; 2016; Lima, Peru.

Silva CS, Lallo MA, Bentubo HDL. Megabacteriose aviária: breve revisão. Res Soc Develop. 2022;11(1):e20211125146. doi:10.33448/rsd-v11i1.25146.

Van Herck H, Duijser T, Zwart P, Dorrestein GM, Buitelaar M, Van Der Hage MH. A bacterial proventriculitis in canaries (Serinus canaria). Avian Pathol. 1984 Jul;13(3):561-72. doi: 10.1080/03079458408418555. PMID: 18766868.

Marlier D, Leroy C, Sturbois M, Delleur V, Poulipoulis A, Vindevogel H. Increasing incidence of megabacteriosis in canaries (Serinus canarius domesticus). Vet J. 2006 Nov;172(3):549-52. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.07.006. Epub 2005 Sep 2. PMID: 16140025.

Babazadeh, D., Ghavami, S., Nikpiran, H., Dorestan, N., 2015. Acute megabacteriosis and staphylococosis of canary in Iran. J. World's Poult. Res. 5(1), 19-20.

Lanzarot P, Blanco JL, Alvarez-Perez S, Abad C, Cutuli MT, Garcia ME. Prolonged fecal shedding of 'megabacteria' (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) by clinically healthy canaries (Serinus canaria). Med Mycol. 2013 Nov;51(8):888-91. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.813652. Epub 2013 Jul 16. PMID: 23855411.

Tonelli A. Megabacteriosis in exhibition budgerigars. Vet Rec. 1993; 132:492.

Baker JR. Causes of mortality and morbidity in exhibition budgerigars in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1996 Aug 17;139(7):156-62. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.7.156. PMID: 8870200.

Filippich LJ, Hendrikz JK. Prevalence of megabacteria in budgerigar colonies. Aust Vet J. 1998 Feb;76(2):92-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1998.tb14533.x. PMID: 9578775.

Talazadeh F, Ghorbanpoor M, Bahadori Y. Avian gastric yeast (macrorhabdosis) in cockatiel, budgerigar and grey parrot: a focus on the clinical signs, molecular detection and phylogenetic evaluation. Vet Res Forum. 2023;14(5):281-287. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2022.551140.3430. Epub 2023 May 15. PMID: 37342288; PMCID: PMC10278900.

Huchzermeyer FW, Henton MM, Keffen RH. High mortality associated with megabacteriosis of proventriculus and gizzard in ostrich chicks. Vet Rec. 1993 Aug 7;133(6):143-4. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.6.143. PMID: 8236692.

Segabinazi SD, Flôres ML, Kommers GD, Barcelos ADS, Veit DC, Eltz RD. (2004). Megabacteriose em emas (Rhea americana) no Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciência Rural, 34, 959-960.

Behnke EL, Fletcher OJ. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (Megabacterium) infection in adult hobby chickens in North America. Avian Dis. 2011 Jun;55(2):331-4. doi: 10.1637/9569-100710-Case.1. PMID: 21793454.

Hanka, K., Koehler, K., Kaleta, E.F., Sommer, D., Burkhardt, E., 2010. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster: Detection in companion birds, poultry and pigeons,morphological characterization and examination of in vitro cultivation. Der. Praktische. Tierarzt. 91, 390-395.

Martins NRS, Horta AC, Siqueira AM, Lopes SQ, Resende JS, Jorge MA, Assis RA, Martins NE, Fernandes AA, Barrios PR, Costa TJR, Guimarães LMC. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in ostrich, rhea, canary, zebra finch, free range chicken, turkey, guinea-fowl, columbina pigeon, toucan, chukar partridge and experimental infection in chicken, Japanese quail and mice. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2006; 58(3):291-298.

Piasecki T, Prochowska S, Celmer Z, Sochacka A, Bednarski M. Occurrence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in exotic and wild birds in Poland. Med. Weter. 2012; 68(4): 245-249.

Blagojević B, Davidov I, Galfi Vukomanović A, Tekić D, Došenović Marinković M, Vidović V. Occurrence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in exotic birds. Pol J Vet Sci. 2024 Mar 20;27(1):139-142. doi: 10.24425/pjvs.2024.149335. PMID: 38511651.

Fulton RM, Mani R. Avian Gastric Yeast (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) and Mycobacterium genavense Infections in a Zoo Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) Flock. Avian Dis. 2020 Dec 1;64(4):561-564. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-64.4.561. PMID: 33647153.

Baker JR. Megabacteria in diseased and healthy budgerigars. Vet Rec. 1997 Jun 14;140(24):627. doi: 10.1136/vr.140.24.627. PMID: 9228694.

Kheirandish R, Salehi M. Megabacteriosis in budgerigars: diagnosis and treatment. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2011; 20:501-5.

Antinoff N, Filippich LJ, Speer B, Powers LV, Phalen DN. Diagnosis and treatment options for megabacteria (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster). J Avian Med Surg. 2004;18(3):189-195.

Baron HR, Stevenson BC, Phalen DN. Comparison of In-Clinic Diagnostic Testing Methods for Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Avian Med Surg. 2021 Apr;35(1):37-44. doi: 10.1647/1082-6742-35.1.37. PMID: 33892587.

Sullivan PJ, Ramsay EC, Greenacre CB, Cushing AC, Zhu X, Jones MP. Comparison of Two Methods for Determining Prevalence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in a Flock of Captive Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). J Avian Med Surg. 2017 Jun;31(2):128-131. doi: 10.1647/2016-213. PMID: 28644084.

Swayne DE. Diseases of poultry. ed. David E. Swayne; 14th ed.,Wiley-Blackwell, 2020.

Poleschinski JM, Straub JU, Schmidt V. Comparison of Two Treatment Modalities and PCR to Assess Treatment Effectiveness in Macrorhabdosis. J Avian Med Surg. 2019 Sep 9;33(3):245-250. doi: 10.1647/2018-358. PMID: 31893619.

Kanno S, Matsumoto Y. Analysis for the diagnostic accuracy of PCR detection of Macrorhabdusin companion birds. Open Vet J. 2023 Dec;13(12):1769-1775. doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2023.v13.i12.26. Epub 2023 Dec 31. PMID: 38292717; PMCID: PMC10824081.

Vrbasova L, Molinkova D, Linhart P, Knotek Z. Verification of accuracy of qPCR method for intravital diagnostics of Macrorhabdus ornithogasterin avian droppings. Vet Med (Praha). 2023 Feb 22;68(2):69-74. doi: 10.17221/85/2022-VETMED. PMID: 38332763; PMCID: PMC10847817.

Kojima A, Osawa N, Oba M, Katayama Y, Omatsu T, Mizutani T. Validation of the usefulness of 26S rDNA D1/D2, internal transcribed spacer, and intergenic spacer 1 for molecular epidemiological analysis of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Vet Med Sci. 2022 Feb 23;84(2):244-250. doi: 10.1292/jvms.21-0576. Epub 2021 Dec 23. PMID: 34937831; PMCID: PMC8920720.

Lang DM, Adamovicz LA, Hung CC, Delk KW, Langan JN, Chinnadurai SK, Allender MC. Development of a validated quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay and fungal culture for the diagnosis of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Am J Vet Res. 2025 Feb 19;86(5):ajvr.24.10.0325. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.24.10.0325. PMID: 39970531.

Amer MM, Mekky HM. Avian gastric yeast (AGY) infection (macrorhabdiosis or megabacteriosis). Bulg J Vet Med. 2020;23(4):397-410.

Schulze C, Heidrich R. Megabakterien-assoziierte Proventrikulitis beim Nutzgeflügel in Brandenburg [Megabacteria-associated proventriculitis in poultry in the state of Brandenburg, Germany]. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2001 Jun;108(6):264-6. German. PMID: 11449914.

Ozmen O, Aydogan A, Haligur M, Adanir R, Kose O, Sahinduran S. The pathology of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster and Eimeria dunsingi (Farr, 1960) infections in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Israel J Vet Med. 2013;68(4):218-224.

Baron HR, Leung KCL, Stevenson BC, Gonzalez MS, Phalen DN. Evidence of amphotericin B resistance in Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in Australian cage-birds. Med Mycol. 2019 Jun 1;57(4):421-428. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy062. PMID: 30085075.

Ledwoń A, Szeleszczuk P, Czopowicz M. Assessment of the efficacy of amphotericin B for reduction of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster shedding in budgerigars. Med Weter. 2016; 72(4):237–239.

Püstow R, Krautwald-Junghanns ME. The Incidence and Treatment Outcomes of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection in Budgerigars ( Melopsittacus undulatus) in a Veterinary Clinic. J Avian Med Surg. 2017 Dec;31(4):344-350. doi: 10.1647/2016-181. PMID: 29327956.

Carpenter JW. Exotic Animal Formulary. 6th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2023.

Phalen DN. Common bacterial and fungal infectious diseases in pet birds. Suppl Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2003;25:43-48.

Hannafusa Y, Bradley A, Tomaszewski EE, Libal MC, Phalen DN. Growth and metabolic characterization of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007 May;19(3):256-65. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900305. PMID: 17459854.

Sruthy Chandran B, Ambily R, Mini M, Surya S. Isolation and identification of avian gastric yeast from a flock of captive budgerigars in Kerala. J Indian Vet Assoc. 2024;22(1):62-67.

Queirós TS, Carvalho PR, Pita MCG. Megabacteriosis: Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in bird – review. Pubvet. 2011;5:1080.

Kafrashi MH, Babazadeh D. Detection and prospects of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (avian gastric yeast; megabacteriosis) obtained from symptomatic companion birds in Aria Veterinary Hospital, Mashhad, Iran, during 2021-2022. J World's Poult Sci. 2022;1(1):29-31.

Đuričić D. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster-associated Avian Macrorhabdosis: A Narrative Review. IgMin Res. May 06, 2025; 3(5): 211-216. IgMin ID: igmin301; DOI:10.61927/igmin301; Available at: igmin.link/p301

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Department of Poultry Diseases with Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb, Heinzelova 55, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia

Address Correspondence:

Đuričić D, Department of Poultry Diseases with Clinic, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Zagreb, Heinzelova 55, 10000 Zagreb, Croatia, Email: [email protected]

How to cite this article:

Đuričić D. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster-associated Avian Macrorhabdosis: A Narrative Review. IgMin Res. May 06, 2025; 3(5): 211-216. IgMin ID: igmin301; DOI:10.61927/igmin301; Available at: igmin.link/p301

Copyright: © 2025 Đuričić D This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Table 1: Clinical Signs of Macrorhabdosis...

Table 1: Clinical Signs of Macrorhabdosis...

Scanlan CM, Graham DL. Characterization of a gram-positive bacterium from the proventriculus of budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Avian Dis. 1990 Jul-Sep;34(3):779-86. PMID: 2241708.

Horvatek Tomić D, Lukač M, Lozica L, Budicin E, Gottstein Ž. Avian macrorhabdosis – a well-known disease with a new name. Hrvatski veterinarski vjesnik. 2024;32(1):29-33.

Werther, K., Schocken-Iturrino, R.P., Verona, C.E.S., Barros, L.S.S., 2000. Megabacteriosis occurrence in budgerigars, canaries and lovebirds in Ribeirão Preto region-Sao Paulo state-Brazil. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2(2), 183-187.

Gerlach H. Megabacteriosis. Semin. Avian Exotic Pet Med. 2001; 10:12-19.

Ravelhofer-Rotheneder K, Engelhardt H, Wolf O, Amann R, Breuer W, Kösters J. Taxonomic classification of megabacterial isolates from budgerigars (Mellopsittacus undulatus Shaw, 1805). Tierärztl. Prax. 2000; 28:415-420.

Tomaszewski EK, Logan KS, Snowden KF, Kurtzman CP, Phalen DN. Phylogenetic analysis identifies the 'megabacterium' of birds as a novel anamorphic ascomycetous yeast, Macrorhabdus ornithogaster gen. nov., sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003 Jul;53(Pt 4):1201-1205. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.02514-0. PMID: 12892150.

Abd El-Ghany W. Avian macrorhabdosis (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) causing proventriculitis: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and control: Vet. Integr Sci. 2024;22(3):921-31.

Phalen DN. Update on the diagnosis and management of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (formerly megabacteria) in avian patients. Vet Clin North Am Exot Anim Pract. 2014 May;17(2):203-10. doi: 10.1016/j.cvex.2014.01.005. PMID: 24767742.

Powers LV, Mitchell MA, Garner MM. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection and Spontaneous Proventricular Adenocarcinoma in Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Vet Pathol. 2019 May;56(3):486-493. doi: 10.1177/0300985818823773. Epub 2019 Jan 16. PMID: 30651051.

Borrelli L, Dipineto L, Rinaldi L, Romano V, Noviello E, Menna LF, Cringoli G, Fioretti A. New Diagnostic Insights for Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection. J Clin Microbiol. 2015 Nov;53(11):3448-50. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01564-15. Epub 2015 Aug 19. PMID: 26292316; PMCID: PMC4609710.

Luján Vega C, Gonzales-Gustavson E, Alfonso C. Detection of avian gastric yeast (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) in exotic small psittacines and passerines of aviaries in Lima, Peru. Presented at: Latin American Veterinary Conference; 2016; Lima, Peru.

Silva CS, Lallo MA, Bentubo HDL. Megabacteriose aviária: breve revisão. Res Soc Develop. 2022;11(1):e20211125146. doi:10.33448/rsd-v11i1.25146.

Van Herck H, Duijser T, Zwart P, Dorrestein GM, Buitelaar M, Van Der Hage MH. A bacterial proventriculitis in canaries (Serinus canaria). Avian Pathol. 1984 Jul;13(3):561-72. doi: 10.1080/03079458408418555. PMID: 18766868.

Marlier D, Leroy C, Sturbois M, Delleur V, Poulipoulis A, Vindevogel H. Increasing incidence of megabacteriosis in canaries (Serinus canarius domesticus). Vet J. 2006 Nov;172(3):549-52. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2005.07.006. Epub 2005 Sep 2. PMID: 16140025.

Babazadeh, D., Ghavami, S., Nikpiran, H., Dorestan, N., 2015. Acute megabacteriosis and staphylococosis of canary in Iran. J. World's Poult. Res. 5(1), 19-20.

Lanzarot P, Blanco JL, Alvarez-Perez S, Abad C, Cutuli MT, Garcia ME. Prolonged fecal shedding of 'megabacteria' (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) by clinically healthy canaries (Serinus canaria). Med Mycol. 2013 Nov;51(8):888-91. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2013.813652. Epub 2013 Jul 16. PMID: 23855411.

Tonelli A. Megabacteriosis in exhibition budgerigars. Vet Rec. 1993; 132:492.

Baker JR. Causes of mortality and morbidity in exhibition budgerigars in the United Kingdom. Vet Rec. 1996 Aug 17;139(7):156-62. doi: 10.1136/vr.139.7.156. PMID: 8870200.

Filippich LJ, Hendrikz JK. Prevalence of megabacteria in budgerigar colonies. Aust Vet J. 1998 Feb;76(2):92-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1998.tb14533.x. PMID: 9578775.

Talazadeh F, Ghorbanpoor M, Bahadori Y. Avian gastric yeast (macrorhabdosis) in cockatiel, budgerigar and grey parrot: a focus on the clinical signs, molecular detection and phylogenetic evaluation. Vet Res Forum. 2023;14(5):281-287. doi: 10.30466/vrf.2022.551140.3430. Epub 2023 May 15. PMID: 37342288; PMCID: PMC10278900.

Huchzermeyer FW, Henton MM, Keffen RH. High mortality associated with megabacteriosis of proventriculus and gizzard in ostrich chicks. Vet Rec. 1993 Aug 7;133(6):143-4. doi: 10.1136/vr.133.6.143. PMID: 8236692.

Segabinazi SD, Flôres ML, Kommers GD, Barcelos ADS, Veit DC, Eltz RD. (2004). Megabacteriose em emas (Rhea americana) no Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Ciência Rural, 34, 959-960.

Behnke EL, Fletcher OJ. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (Megabacterium) infection in adult hobby chickens in North America. Avian Dis. 2011 Jun;55(2):331-4. doi: 10.1637/9569-100710-Case.1. PMID: 21793454.

Hanka, K., Koehler, K., Kaleta, E.F., Sommer, D., Burkhardt, E., 2010. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster: Detection in companion birds, poultry and pigeons,morphological characterization and examination of in vitro cultivation. Der. Praktische. Tierarzt. 91, 390-395.

Martins NRS, Horta AC, Siqueira AM, Lopes SQ, Resende JS, Jorge MA, Assis RA, Martins NE, Fernandes AA, Barrios PR, Costa TJR, Guimarães LMC. Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in ostrich, rhea, canary, zebra finch, free range chicken, turkey, guinea-fowl, columbina pigeon, toucan, chukar partridge and experimental infection in chicken, Japanese quail and mice. Arq. Bras. Med. Vet. Zootec. 2006; 58(3):291-298.

Piasecki T, Prochowska S, Celmer Z, Sochacka A, Bednarski M. Occurrence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in exotic and wild birds in Poland. Med. Weter. 2012; 68(4): 245-249.

Blagojević B, Davidov I, Galfi Vukomanović A, Tekić D, Došenović Marinković M, Vidović V. Occurrence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in exotic birds. Pol J Vet Sci. 2024 Mar 20;27(1):139-142. doi: 10.24425/pjvs.2024.149335. PMID: 38511651.

Fulton RM, Mani R. Avian Gastric Yeast (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster) and Mycobacterium genavense Infections in a Zoo Budgerigar (Melopsittacus undulatus) Flock. Avian Dis. 2020 Dec 1;64(4):561-564. doi: 10.1637/0005-2086-64.4.561. PMID: 33647153.

Baker JR. Megabacteria in diseased and healthy budgerigars. Vet Rec. 1997 Jun 14;140(24):627. doi: 10.1136/vr.140.24.627. PMID: 9228694.

Kheirandish R, Salehi M. Megabacteriosis in budgerigars: diagnosis and treatment. Comp. Clin. Pathol. 2011; 20:501-5.

Antinoff N, Filippich LJ, Speer B, Powers LV, Phalen DN. Diagnosis and treatment options for megabacteria (Macrorhabdus ornithogaster). J Avian Med Surg. 2004;18(3):189-195.

Baron HR, Stevenson BC, Phalen DN. Comparison of In-Clinic Diagnostic Testing Methods for Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Avian Med Surg. 2021 Apr;35(1):37-44. doi: 10.1647/1082-6742-35.1.37. PMID: 33892587.

Sullivan PJ, Ramsay EC, Greenacre CB, Cushing AC, Zhu X, Jones MP. Comparison of Two Methods for Determining Prevalence of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in a Flock of Captive Budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). J Avian Med Surg. 2017 Jun;31(2):128-131. doi: 10.1647/2016-213. PMID: 28644084.

Swayne DE. Diseases of poultry. ed. David E. Swayne; 14th ed.,Wiley-Blackwell, 2020.

Poleschinski JM, Straub JU, Schmidt V. Comparison of Two Treatment Modalities and PCR to Assess Treatment Effectiveness in Macrorhabdosis. J Avian Med Surg. 2019 Sep 9;33(3):245-250. doi: 10.1647/2018-358. PMID: 31893619.

Kanno S, Matsumoto Y. Analysis for the diagnostic accuracy of PCR detection of Macrorhabdusin companion birds. Open Vet J. 2023 Dec;13(12):1769-1775. doi: 10.5455/OVJ.2023.v13.i12.26. Epub 2023 Dec 31. PMID: 38292717; PMCID: PMC10824081.

Vrbasova L, Molinkova D, Linhart P, Knotek Z. Verification of accuracy of qPCR method for intravital diagnostics of Macrorhabdus ornithogasterin avian droppings. Vet Med (Praha). 2023 Feb 22;68(2):69-74. doi: 10.17221/85/2022-VETMED. PMID: 38332763; PMCID: PMC10847817.

Kojima A, Osawa N, Oba M, Katayama Y, Omatsu T, Mizutani T. Validation of the usefulness of 26S rDNA D1/D2, internal transcribed spacer, and intergenic spacer 1 for molecular epidemiological analysis of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Vet Med Sci. 2022 Feb 23;84(2):244-250. doi: 10.1292/jvms.21-0576. Epub 2021 Dec 23. PMID: 34937831; PMCID: PMC8920720.

Lang DM, Adamovicz LA, Hung CC, Delk KW, Langan JN, Chinnadurai SK, Allender MC. Development of a validated quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay and fungal culture for the diagnosis of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Am J Vet Res. 2025 Feb 19;86(5):ajvr.24.10.0325. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.24.10.0325. PMID: 39970531.

Amer MM, Mekky HM. Avian gastric yeast (AGY) infection (macrorhabdiosis or megabacteriosis). Bulg J Vet Med. 2020;23(4):397-410.

Schulze C, Heidrich R. Megabakterien-assoziierte Proventrikulitis beim Nutzgeflügel in Brandenburg [Megabacteria-associated proventriculitis in poultry in the state of Brandenburg, Germany]. Dtsch Tierarztl Wochenschr. 2001 Jun;108(6):264-6. German. PMID: 11449914.

Ozmen O, Aydogan A, Haligur M, Adanir R, Kose O, Sahinduran S. The pathology of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster and Eimeria dunsingi (Farr, 1960) infections in budgerigars (Melopsittacus undulatus). Israel J Vet Med. 2013;68(4):218-224.

Baron HR, Leung KCL, Stevenson BC, Gonzalez MS, Phalen DN. Evidence of amphotericin B resistance in Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in Australian cage-birds. Med Mycol. 2019 Jun 1;57(4):421-428. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myy062. PMID: 30085075.

Ledwoń A, Szeleszczuk P, Czopowicz M. Assessment of the efficacy of amphotericin B for reduction of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster shedding in budgerigars. Med Weter. 2016; 72(4):237–239.

Püstow R, Krautwald-Junghanns ME. The Incidence and Treatment Outcomes of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster Infection in Budgerigars ( Melopsittacus undulatus) in a Veterinary Clinic. J Avian Med Surg. 2017 Dec;31(4):344-350. doi: 10.1647/2016-181. PMID: 29327956.

Carpenter JW. Exotic Animal Formulary. 6th ed. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2023.

Phalen DN. Common bacterial and fungal infectious diseases in pet birds. Suppl Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet. 2003;25:43-48.

Hannafusa Y, Bradley A, Tomaszewski EE, Libal MC, Phalen DN. Growth and metabolic characterization of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007 May;19(3):256-65. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900305. PMID: 17459854.

Sruthy Chandran B, Ambily R, Mini M, Surya S. Isolation and identification of avian gastric yeast from a flock of captive budgerigars in Kerala. J Indian Vet Assoc. 2024;22(1):62-67.

Queirós TS, Carvalho PR, Pita MCG. Megabacteriosis: Macrorhabdus ornithogaster in bird – review. Pubvet. 2011;5:1080.

Kafrashi MH, Babazadeh D. Detection and prospects of Macrorhabdus ornithogaster (avian gastric yeast; megabacteriosis) obtained from symptomatic companion birds in Aria Veterinary Hospital, Mashhad, Iran, during 2021-2022. J World's Poult Sci. 2022;1(1):29-31.